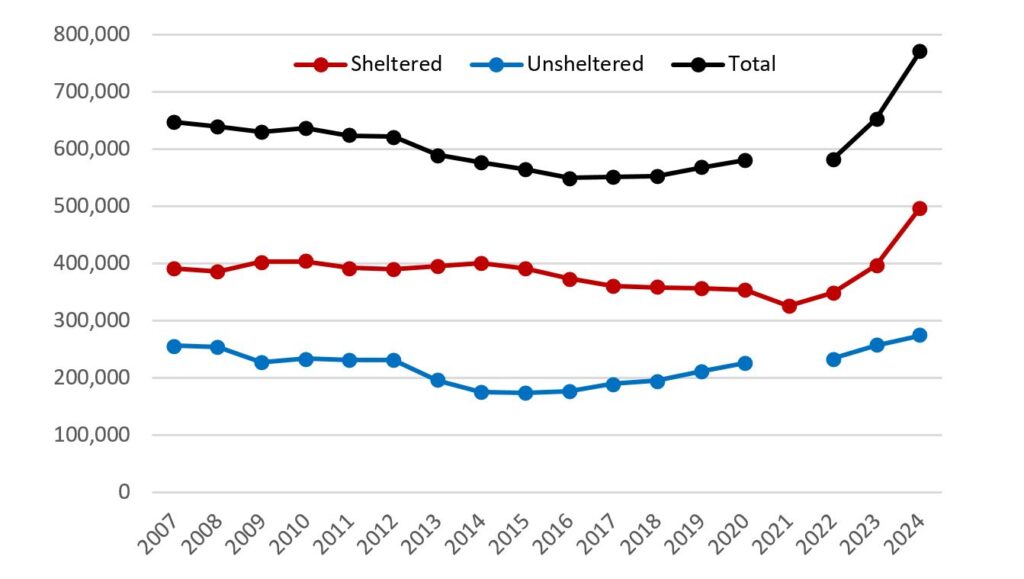

The annual United States homeless population estimates for 2024 were released last week. Homelessness grew by a record 18% annually in 2024, following a then record 12% increase in 2023. As shown in the figure below, the recent spike in homelessness is unprecedented. Going back 17 years since national homeless counts began, homelessness never before grew by more than 3% in a single year.

Figure 1. Total, Sheltered and Unsheltered Homeless Population, United States, 2007–2024

Source: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “The 2024 Annual Homelessness Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress.”

Why is homelessness growing so quickly, and how can we reverse it?

The main reason homelessness grew so quickly over the past two years is the influx of migrants into the United States who have overwhelmed homeless shelters in a handful of areas. Sheltered homelessness grew by just under 150,000 people over the past two years. That represents a 43% increase, which is approximately 10 times as large as the second largest two-year increase on record, when sheltered homelessness grew by 4% from 2008–2010.

From 2022–2024, the areas with the largest increases in sheltered homelessness were places recognized as taking in large numbers of migrants, including New York City (77,352), Chicago (14,590), the Massachusetts “Balance of State” Continuum of Care (8,100), and Metropolitan Denver (6,556). The increase in sheltered homelessness in these four areas totaled approximately 107,000, or 72% of the total increase in the United States from 2022–2024. If we include the entire state of Massachusetts (which may better encompass all of the areas taking in migrants than solely the “Balance of State” Continuum of Care), these areas represent an even higher 75% of the total increase. Sheltered homelessness approximately doubled or more in each of these areas, including a more than five-fold increase in Chicago.

The area with the next highest increase in sheltered homelessness was the Hawaii “Balance of State” Continuum of Care (5,236), which includes the island of Maui where fires displaced thousands of residents and resulted in an 8-fold increase in the sheltered homeless population. If sheltered homelessness in New York City, Chicago, Massachusetts, Metropolitan Denver, and the Hawaii “Balance of State” Continuum of Care had grown at the same rate as the rest of the county, then sheltered homelessness would have grown by only 12% nationally over the past two years, about one fourth as much as the actual 43% increase.

While the migrant crisis explains the unprecedented rise in sheltered homelessness, it does not explain the 17% rise in unsheltered homelessness over the past two years. The same four places that experienced the largest increases in sheltered homelessness saw their unsheltered homeless populations collectively rise by 33%, almost double the national average of 17%, but comprising only about a twentieth of the national rise in unsheltered homelessness from 2022–2024.

Rather, the rise in unsheltered homelessness over the past two years is a continuation of the trend since 2015. The average annual rise in unsheltered homeless from 2015–2020 is 6%, only modestly lower than the 8% annual average increase from 2022–2024. While there are competing explanations for the upward trend, one potential cause is relaxed enforcement of quality of life ordinances in many areas, reducing pressure on unsheltered homeless individuals to come indoors.

What can we do about the growing homelessness problem?

Reducing the sheltered homeless population requires gaining control of the border and controlling the influx of migrants into the United States. Overloading the homeless response system in a few select cities is not sustainable. These systems are intended to respond to housing emergencies facing local residents, not to house migrants from other countries.

The best approach to reducing the unsheltered homeless population is less clear and may require multiple strategies. A combination of increased pressure to move off the street and more effective shelter and housing options once individuals come indoors is likely needed.

One strategy that is unlikely to work is the one touted by the Biden Administration in the press release for the annual homelessness report. They advocate for an increase in permanent supportive housing, offering as evidence the reduction in veteran homelessness over the past couple decades in conjunction with a large expansion of housing targeted specifically to homeless veterans. Acting Secretary of the Department of Housing and Urban Development Adrianne Todman states: “We know what works and our success in reducing veteran homelessness by 55.2% since 2010 shows that.”

The problem with the Biden Administration’s argument is that the reduction in veteran homelessness is more likely due to demographic shifts than policies. Columbia economist Brendan O’Flaherty has pointed out that the number of veterans aged 18–64 has fallen dramatically over the same period in which the number of homeless veterans has declined. Since homelessness becomes much more rare starting at age 65 (as individuals become eligible for more income supports), the decline in veteran homelessness may simply be an artifact of there being fewer veterans below age 65 when homelessness is more likely.

Consistent with this view, in research published in 2017 I found only modest effects of permanent supportive housing on homeless populations. Thus, policymakers should not expect that further expansions of the stock of permanent supportive housing, which has already more than doubled since 2007, will on its own substantially reduce the size of the homeless population.

The surge in homelessness over the past two years is alarming. Fortunately, it can be reversed, by better controlling the border, and by bringing unsheltered homeless people indoors and more effectively addressing their problems when they get there.