As part of Congressional Republicans’ drive to craft “one big beautiful bill” reflecting Donald Trump’s tax and spending agenda, the House Agriculture committee on May 14 approved several proposals that would reduce federal spending by shifting some current federal welfare costs to states. At the same time, dissatisfied conservative members have called for more federal cost shifting, especially under the Medicaid program. The case for such cost shifting starts with disproportionate current federal funding for welfare benefits. But supporters of the status quo also should be challenged to explain why blue states are far more likely to maintain large welfare caseloads under current rules.

The case for reform starts with the perverse incentives for excessive benefit collection embedded in current federal welfare policies. For example, under the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), commonly known as food stamps, federal taxpayers now cover 100 percent of benefit costs. That policy offers an open-ended stream of federal funding for bigger benefit caseloads than states might otherwise choose to maintain if they bore some of the benefit costs themselves.

In contrast, the House Agriculture Committee has approved reconciliation legislation that “would require all States to contribute 5 percent of the cost of SNAP allotments beginning in fiscal year 2028,” and 15, 20, or 25 percent in states with elevated SNAP error rates. As a committee summary notes, this change would align “SNAP with other state-administered entitlement programs by requiring states to shoulder a share of the benefit costs…incentivizing States to administer SNAP more efficiently and effectively.” Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates suggest these changes will yield the largest savings in the Agriculture Committee’s share of the legislation, at $128 billion out of the gross $300 billion the committee legislation is projected to save over the next decade.

In a similar fashion, Medicaid “expansion” policies—which cover nearly all adults with incomes up to 138 percent of the federal poverty line—presently provide states “with an enhanced federal matching rate (FMAP) of 90% for their expansion populations.” That enhanced FMAP significantly exceeds the federal reimbursement rate for other Medicaid recipients, including children, pregnant women, seniors, and disabled individuals, which varies by state from 50 to 83 percent. As a testament to the power of the enhanced match, nine of 41 expansion states have trigger laws that would automatically terminate the expansion if the share of federal funding dropped. Further, according to KFF, “the substantial loss of federal funding would likely force all states to reassess whether to continue the expansion coverage.”

The House Energy and Commerce Committee has adopted a series of changes designed to reduce fraud and abuse and otherwise tighten Medicaid eligibility. Notably, those policies did not include lowering the FMAP rate for the entire expansion population, as conservative members have recommended and CBO has estimated would save “$710 billion over the 2025–2034 period.” The committee did, however, block new expansion states and reduce the FMAP for current expansion states that also provide health coverage to illegal aliens, yielding comparatively modest savings from those policies. Overall, CBO has confirmed the Energy and Commerce legislation achieves its target of saving $880 billion over the next decade.

To state the obvious, placing all, or nearly all, of the financial burden for benefit payments on federal taxpayers contributes to swollen caseloads, as it subsidizes state policy choices that promote greater benefit receipt. Examples of such policy choices include waiving work requirements, adopting broader eligibility standards (such as “broad-based categorical eligibility” for SNAP), and covering individuals whose immigration status has not been verified. The reconciliation legislation addresses some but not all of these current policy choices.

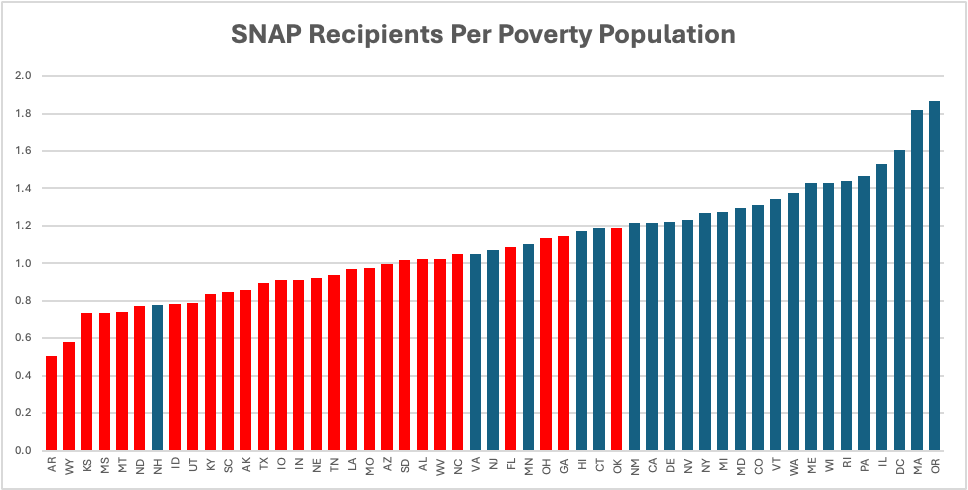

Under current law, blue states dominate where SNAP receipt is greatest, as measured by the percentage of the population in poverty receiving food stamps in January 2025 (the most recent month of data). As displayed in Figure 1 below, all of the top 18 states (including DC) by that measure are blue states, with all providing food stamps to significant shares of their population that are not in poverty. On the flip side, 23 of the bottom 24 states according to the same measure are red states, where SNAP caseloads are significantly lower.

Figure 1. Food Stamp Caseload as a Percentage of Population in Poverty, by State, January 2025

Source: Department of Agriculture and Census Bureau poverty data. Population in poverty reflects state average for 2021-2023.

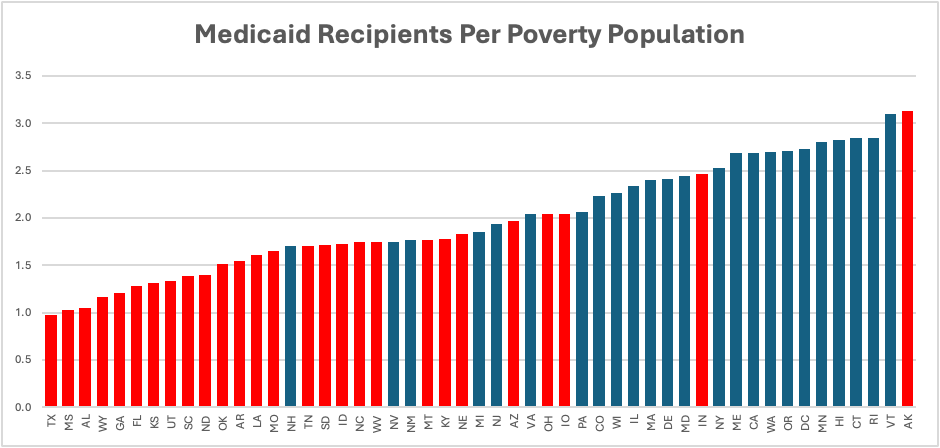

Medicaid’s current benefit rolls display a similar strongly partisan tilt. As displayed in Figure 2 below, 18 of the top 20 states (including DC) by current Medicaid recipients as a share of their population in poverty are blue states, with the exceptions being red Alaska and Indiana. Compared with SNAP, Medicaid receipt also extends far higher up the income ladder. The top 12 states (all blue with the exception of red Alaska) include 2.5 or more Medicaid recipients per person in poverty—reflecting how in those states significantly more Medicaid recipients have incomes above the official poverty line than the state has residents below it. As with SNAP, red states dominate where Medicaid receipt is relatively lower as a share of residents in poverty.

Figure 2. Medicaid Caseload as a Percentage of Population in Poverty, by State, December 2024

Source: Medicaid.gov and Census Bureau poverty data. Population in poverty reflects state average for 2021-2023. Rhode Island value reflects November 2024.

Beyond the question of how current federal funding rules contribute to elevated benefit rolls, some argue that states simply cannot afford to bear additional benefit costs. For example, the Center on Budget Policy Priorities argued in March 2025 that expecting states to bear some SNAP costs “would hit state budgets hard at a time when state finances are already highly strained.” That view ignores the findings of a recent fiscal survey of states conducted by the National Association of State Budget Officers (NASBO). That survey concluded that most states have growing rainy day funds, whose median balance as a percentage of state general fund expenditures “has grown every year since the aftermath of the Great Recession.” According to NASBO, the median balance is expected to grow to “14.4 percent at the end of fiscal 2025.”

Those significant state rainy day funds contrast sharply with federal finances, which are defined by deep current and future deficits, driven by rapidly growing entitlement commitments and interest on the debt. That grim federal fiscal outlook suggests that, even if cost shifts are not enacted through this reconciliation legislation, in the long run federal policymakers will have no choice but to transition to greater state financial responsibility for programs like SNAP and Medicaid. If that transition begins soon, changes can be phased in gradually, limiting disruptions from more abrupt changes that can be expected in response to a debt crisis. That gradual transition would also give states time to develop and implement policies promoting work over benefit collection, minimizing otherwise growing burdens on state taxpayers.

Such improvements are not without precedent. When welfare reforms in the 1990s placed increased financial responsibility on states, states responded by implementing changes that increased work and reduced caseloads, yielding significant savings for both state and federal taxpayers. But those outcomes first required federal reforms that made states more sensitive to the cost of maintaining large welfare caseloads.

States can and should similarly pick up more of the tab for SNAP and Medicaid benefits today. Doing so would hold states more accountable for achieving real results like promoting work and independence from benefits, instead of simply subsidizing bigger benefit caseloads. Unnecessary benefit dependence does no one any good, including recipients who would be better off working as well as taxpayers forced to pick up the tab for it all.