A headline in the Wall Street Journal earlier this year read, “America Is Binging on Snacks, and Food Companies Are Eating It Up.” The article explains how American diets that were already heavily reliant on snacks and packaged foods, have only gotten more so since the pandemic – to the tune of $181 billion in household snack purchases in 2022, up 11% in one year. According to Wall Street Journal reporting, snack companies are doubling down on their snacking strategy, while other traditional food companies are looking to enter the snack food market to capitalize on the “snackification” of the U.S. diet.

While America’s fondness for snacks may be a boon for some food companies, it also spells trouble in several ways. Diet-related disease in the U.S., such as diabetes and heart disease, already far surpass levels of disease in peer countries, with research identifying processed foods such as snacks as a main contributor. Research has also increasingly linked processed foods to mental health problems, such as depression and cognitive decline. And beyond these obvious concerns over health, an American diet further reliant on processed snacks threatens the country’s natural resources and our nation’s traditional farmers in ways that we are only recently becoming aware of.

To reverse these trends, we must create a food system that encourages diets full of fresh fruits, vegetables, grains, unsweetened dairy products and unprocessed meat while limiting processed foods full of sugar, sodium and other additives. Despite myriad federal efforts—including a Surgeon General’s Call to Action in 2001, numerous revisions to the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, and a Presidential National Strategy to Reduce Child Obesity in 2010—increasing demand for healthy foods has proven virtually impossible. However, the federal government has failed to use all of the tools at its disposal, and in some ways has contributed to the problem through its agriculture policies.

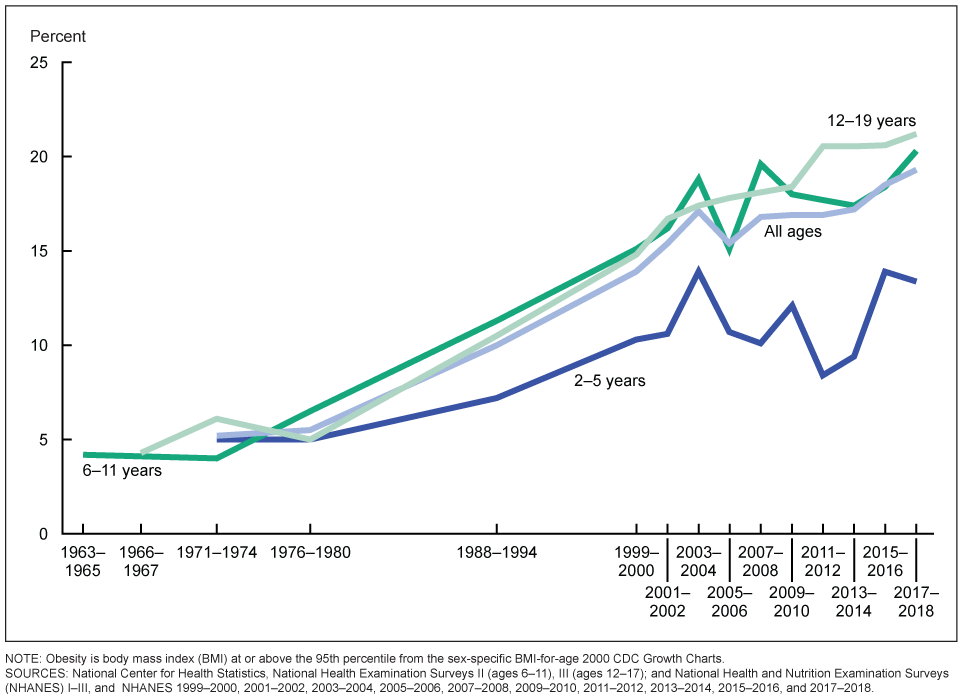

Chart: Trends in obesity among U.S. children and adolescents aged 2–19 years

NOTE: Obesity is body mass index (BMI) at or above the 95th percentile from the sex-specific BMI-for-age 2000 CDC Growth Charts. Source: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/obesity-child-17-18/obesity-child.htm.

Although broader U.S. agriculture policy is beyond the scope of this essay, the federal government’s support for domestic sugar production and corn subsidies likely influences the market for processed foods, leading to overconsumption and poor health. Policies around agriculture subsidies in the U.S. are complex with many competing interests, but lawmakers must consider the broader impact of farm subsidies on health and the ultimate costs. Moving away from policies that make processed food production less costly should be a priority for Congress.

Another tool at the federal government’s disposal is to use federal nutrition assistance programs to bolster consumer demand for fresh foods, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly food stamp program), while sending a message about proper nutrition.

Limited government proponents like myself might ask: Why should the federal government try to influence consumer behavior at all? Isn’t the private market simply meeting consumer demand for processed foods?

While true, the downstream effects of an American diet reliant on unhealthy food is threatening the nation’s competitiveness in the world and is having devastating effects on the country’s overall well-being. While the federal government has no ground to dictate private behavior, the government has a responsibility to ensure its foremost nutrition assistance program is actually meeting the intended goal of improving nutrition.

Yet, the stats are clear. Only one in three American adults are of a healthy weight, and the obesity rate among U.S. children sits at an alarming 21%. The consequences associated with obesity includes diabetes (which almost 15% of U.S. adults have) and hypertension (afflicting 45% of U.S. adults), with diagnosed disease only one of the adverse outcomes associated with unhealthy weight. Recent research shows that these problems disproportionately affect the low-income Americans served by federal nutrition programs—making them a particularly useful tool for improving the health and wellbeing of Americans.

Being overweight or obese negatively affects most aspects of life: labor force participation, mobility, quality of life, work productivity and mental health. In fact, excluding stay-at-home parents, the most common reason prime-age people outside of the labor force give for not working is ill health or disability, with diet quality undoubtedly playing a role.

Further, the costs associated with treating obesity and diet-related disease in the U.S. hits everyone’s pocketbooks. One study estimated the total medical costs in the U.S. associated with treating obesity was $260 billion in 2016 – equating to $1000 per U.S. adult every year – which raises health insurance costs for everyone. Another study found that the costs of diet-related cardiovascular disease and diabetes alone tops $50 billion per year in health care costs. These estimates do not even consider the costs of new obesity drugs, which have proven effective but expensive, nor the indirect costs associated with obesity and diet-related disease such as lost work time and limited employment.

Consider also the effects of the average American diet on our environment. Experts argue that a heavy reliance on processed foods “are the major driver of poor health and environmental degradation.” Research has found that “Western diets – dominated by processed foods, refined sugar, fats and flours” negatively affects health, agricultural production and the environment, explaining that diets dominated by unhealthy processed foods rely on “methods of agricultural production that negatively impact ecosystems, increase the use of fossil fuels and boost greenhouse gas emissions.” In one study, researchers categorized 170 different countries based on their dominant food system type. Animal source and sugar food systems dominated among high-income countries (like the US), and were associated with a larger environmental footprint, including production of more greenhouse gases, more freshwater use and land use.

A shift away from a U.S. diet full of processed foods could also be good for farmers by encouraging crop diversification. Crop diversification allows farmers to spread risk across a variety of crops (without federal insurance or subsidies) and be more competitive in the market. It can also help farmers preserve their land, making it productive over more years. As the authors of an article in the American Journal of Public Health argued in 2019: “Dietary choices determine more than health.”

Furthermore, farming experts believe that “more diverse farms can support healthy diets in several different ways.” Experts describe the benefits of crop diversification – such as less land use and fewer fossil fuels – and the potential advantages for individual health. Traditional farming can be lucrative for small and medium-sized farms when demand for their products exists on a large scale. Reversing the harmful trends toward more processed snack foods in the American diet will not only improve health but will also create a tremendous opportunity for local farmers and for conservationists.

We are reaching a crisis point: What we put in our bodies and our land is threatening the nation’s general well-being.

Granted, these problems are so big that they require a multi-faceted approach. But the federal government’s nutrition assistance policies can play a major role by informing Americans what constitutes proper nutrition and by leveraging billions of federal food assistance dollars to increase demand for healthy foods.

The federal government’s National School Lunch Program (NSLP)—serving over 30 million children per school day—already sets nutrition standards for what schools can serve as part of the program. Reforms in 2012 required participating schools to offer more fruits and vegetables, whole grains and low fat milk, while reducing the amount of sodium and saturated fats in available foods. Research showed that those changes not only led to healthier meal offerings, but they also improved what children consumed based on their healthy index scores. However, the NSLP is relatively small in scale. Although it reaches many students, the total budget is under $15 billion per year. Similarly, the Special Supplemental Food Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) also sets clear nutrition standards, but the total budget falls under $6 billion per year.

In contrast, SNAP provides more than $100 billion in food benefits to low-income families each year and covers 40 million people, approximately 12% of the US population. Yet, the program has no nutritional standards and participants spend a sizeable share of benefits (at least 25%) on unhealthy foods such as sugary beverages, frozen prepared foods, prepared desserts and candy.

One way to increase demand for healthy foods is to transform how SNAP administers benefits. By restricting the use of SNAP benefits to conform with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGAs), millions of Americans will experience improved diets. Because SNAP covers a sizeable share of the population, increased demand for healthy foods among program participants could influence the purchases of those higher up the income scale as well.

Currently, the USDA determines the maximum SNAP benefit for each household size using the “Thrifty Food Plan,” defined as the estimated cost of “a nutritious, practical, cost-effective diet prepared at home.” The Thrifty Food Plan balances the DGAs with constraints on time and convenience, leading the Plan to incorporate calorie-dense processed foods. Furthermore, even though the Thrifty Food Plan is supposed to represent a nutritious diet, there is no requirement that SNAP participants use their benefits to purchase those foods.

Under my plan, researchers would still estimate the cost of a “Thrifty Food Plan” (see this primer on the Thrifty Food Plan) to set SNAP benefit levels, but the only constraint would be the DGAs. SNAP benefits would be divided into two categories – “green” benefits to be used only for DGAs recommended foods, including minimally processed vegetables, fruits, grains, proteins, oils and unsweetened dairy. SNAP participants could use “red” benefits for anything else. Research would inform the proper distribution of benefits between the two groups. If, for example, 75% of monthly SNAP benefits were allocated for “green” foods, then 75% of each households benefits would be restricted to purchasing foods that fit into that category.

While classifying every food into categories may sound overly complicated, SNAP could rely on the NOVA food classification system to determine what constitutes a “green” food versus a “red” food. And the new system could utilize digital currency and store level technology to track food purchases. Many states already use ConnectEBT, which allows SNAP participants to monitor benefit use through a mobile app. Linking this type of mobile application to SNAP retailer Point-of-Sale (POS) systems would allow SNAP participants to monitor their green and red purchases and track the foods they purchase over time.

Additionally, SNAP retailers would be encouraged to market their products according to whether they are SNAP-eligible or not, which essentially translates into a food that the DGAs recommends versus one that the DGAs recommends limiting. Retailers could even place green and red stickers on SNAP-eligible foods, which could also influence other consumers. Finally, the USDA could also simplify the process for becoming a SNAP-retailer for producers of “green” foods, including local farming cooperatives, farmer’s markets, and other fresh produce, meat, and dairy farms.

Moving to this type of SNAP system would be widely unpopular among processed food and sugary beverage companies, but over time it could shift their incentives toward more healthy food production that benefits our health, the environment and our farmers.