The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reported out the latest employment numbers on Friday, August 1, finding that nonfarm establishments added just 73,000 jobs in July compared with June. That was a disappointing number, but the news was worse below the headline. The combined number of jobs the economy added in May and June—previously reported by BLS at 291,000—was revised downward by 258,000 to just 33,000. That is the largest two-month downward revision reported by BLS outside of a recession since 1968.

By the end of the day, President Donald Trump had fired BLS Commissioner Erika McEntarfer. The White House quickly released a memo criticizing her “lengthy history of inaccuracies, incompetence.” It cited multiple instances of revisions to jobs estimates going back to April 2024 and referenced several breaches of data security and data-sharing protocol that occurred in 2024.

But any ambiguity about the specific sins that led to McEntarfer’s fall was cleared up later that afternoon, when Trump took to his preferred social media platform, Truth Social:

In my opinion, today’s Jobs Numbers were RIGGED in order to make the Republicans, and ME, look bad — Just like when they had three great days around the 2024 Presidential Election, and then, those numbers were “taken away” on November 15, 2024, right after the Election, when the Jobs Numbers were massively revised DOWNWARD, making a correction of over 818,000 Jobs — A TOTAL SCAM.

Let’s stipulate that the three operational breaches in question were serious matters. Moreover, the acting secretary of the Department of Labor appears not to have been sufficiently cooperative with House oversight of BLS, and it’s not clear that McEntarfer herself responded to a similar inquiry from Senators Bill Cassidy and Susan Collins.

Even so, the incidents involved mistakes and judgmental lapses on the part of lower-ranking staff rather than intentional wrong-doing by McEntarfer or other senior BLS officials. BLS acknowledged the breaches promptly and looped in the Department of Labor’s inspector general. The incidents in question took place between February and August of last year. The last one drew a Truth Social post, but Trump had not criticized BLS in the ensuing months, before or after becoming president.

In fact, if his social media posts are to be believed, Trump only became aware of McEntarfer after the latest jobs report:

I was just informed that our Country’s “Jobs Numbers” are being produced by a Biden Appointee, Dr. Erika McEntarfer, the Commissioner of Labor Statistics, who faked the Jobs Numbers before the Election to try and boost Kamala’s chances of Victory. This is the same Bureau of Labor Statistics that overstated the Jobs Growth in March 2024 by approximately 818,000 and, then again, right before the 2024 Presidential Election, in August and September, by 112,000. These were Records — No one can be that wrong? We need accurate Jobs Numbers. I have directed my Team to fire this Biden Political Appointee, IMMEDIATELY. She will be replaced with someone much more competent and qualified. Important numbers like this must be fair and accurate, they can’t be manipulated for political purposes. McEntarfer said there were only 73,000 Jobs added (a shock!) but, more importantly, that a major mistake was made by them, 258,000 Jobs downward, in the prior two months. Similar things happened in the first part of the year, always to the negative.

Tellingly, the President’s posts make no mention of the BLS operational missteps—only the revisions to the jobs estimates and the implied political bias behind them. However, far from McEntarfer being guilty of running a political shop, her firing was itself primarily political. The President’s accusations don’t stand up, and his actions should send a chill down the spine of Americans of all ideological stripes.

Understanding the BLS Monthly Employment Revisions

The monthly jobs estimates come from the Current Employment Statistics (CES) program—a massive survey of about 630,000 worksites each month. The first Friday of every month, estimates for the previous month are released on what is often colloquially called Jobs Day. These are hot off the presses—the survey obtains employment information about the pay period the previous month that includes the 12th of the month, so the turnaround time is a tough challenge.

For example, on June 6, BLS reported the initial estimates for May. To do so, it looked at how much employment changed among the subset of establishments that beat the reporting deadline for the May numbers and that also reported April employment. It used this percentage increase to update the April estimate, and it made some model-driven assumptions about how many establishments were created in May and how many closed. The result was the “first preliminary estimate” of nonfarm employment for May.

Employers continue to report to BLS after this first estimate is released, so on Jobs Day the following month, BLS updates them as “second preliminary estimates.” It does the same one month later, releasing “final sample-based estimates.” I’ll just call these numbers the first, second, and third estimates.

The July 3 Jobs Day provided the second employment estimates for May and the first estimates for June. The data indicated that the US economy had added 144,000 nonfarm jobs in May and another 147,000 in June. That May figure was revised up from the 128,000 reported on Jobs Day in June. In the August release, however, the numbers were revised down to 19,000 jobs added in May and 14,000 in June.

These revisions are standard, routine updates. BLS has released these twice-updated estimates since the mid-twentieth century. They are not unusual “mistakes”; they follow initial estimates deemed “preliminary.” When the White House memo criticizing McEntarfer singled out her BLS for releasing initially optimistic estimates “only for those numbers to be quietly revised later,” it unjustifiably cast standard operating procedure in a sinister light.

An important issue for these monthly revisions is that small changes to the employment estimates can produce relatively large changes in the estimates of jobs added. Take the May-to-June jobs added estimate. In last week’s jobs report, the estimate for nonfarm employment in May was revised downward by one-tenth of one percent (actually 0.08 percent). The estimate for June was revised downward by two-tenths of one percent (0.16 percent). But the resulting increase in nonfarm jobs from May to June after these revisions was smaller by over 90 percent than had been reported the previous month.

If the June revision had come in lower by 0.10 percent instead of 0.16 percent, the jobs-added estimate would have shrunk not by 90 percent but by 24 percent. Rather than it being revised downward by 133,000 jobs, it would only have been revised downward by 35,000.

How Have the Monthly Employment Revisions Changed Over Time?

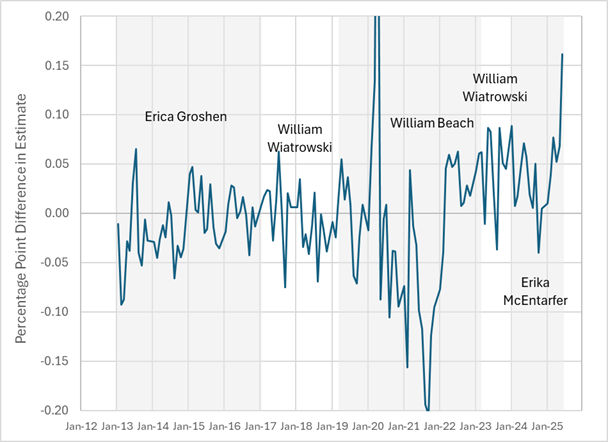

We can assess how the month-to-month revisions have affected the nonfarm employment estimates over time. In Figure 1, I’ve plotted for each month the difference between the first employment estimate and the twice-revised estimate reported two Jobs Days later (the third estimate). This difference is expressed as a percentage of the third estimate, so the figures tell how much the first estimate was too high or low relative to the eventual one. The chart covers over ten years—enough to include McEntarfer’s recent predecessors as BLS commissioner. I have shaded and labeled the chart to indicate the terms served by the various commissioners.

Figure 1. Percentage by Which the First Nonfarm Employment Estimate was Off, Relative to the Twice-Revised Third Estimate, by BLS Commissioner Term

(Positive = First Estimate too High, All Estimates Seasonally Adjusted)

Note: Estimates from the Federal Reserve Board of St. Louis (https://alfred.stlouisfed.org/series/downloaddata?seid=PAYEMS). All of the estimates are seasonally adjusted and are those reported before the benchmark revision. Note that there are no third estimates for November and December that are published separately from the benchmark revision; the third estimate for November and the second and third estimates for December incorporate the benchmark revision. Therefore, for the November points in the chart, I compare the first estimate to the second estimate, and I omit entirely the December points. For June 2025, since we will not know the third estimate until next month, I compare the first and second estimates. The April 2020 and September 2021 points are outliers (0.49 percent and -0.20 percent) and outside the range of the y axis.

An initial point to emphasize is just how small the revisions to the monthly estimates are. Over the past twelve and a half years, the first employment estimate nearly always has been within -0.1 to 0.1 percent of the third estimate. Note that this is not -10 percent to 10 percent; this is off by plus or minus one-tenth of one percent. Only nine estimates fall outside this range.

A second point is that despite the typically small revisions, there has been a trend toward the first estimates overstating employment. Importantly, that trend predates Trump’s current presidency or McEntarfer’s time at BLS. Since March 2022, with just three exceptions, the first estimates have tended to be too high.

We can compare how accurate the first estimates have been across BLS commissioners. Erica Groshen was appointed by President Obama and unanimously confirmed by the Senate. She served her full four-year term, from January 2013 to January 2017. During the 49 months in this span, the first employment estimate was, on average, too low by 0.01 percent relative to the third estimate. That’s pretty much spot-on.

Bill Wiatrowski, a long-time BLS employee, then served as acting commissioner for over half of Trump’s first term, until March 2019. The average accuracy of the first employment estimate was again impressive during these years—undershooting the third estimate by an average of just 0.01 percent over 26 months.

Bill Beach was nominated by President Trump in October 2017, but the Senate did not confirm him until March 2019 (on a divided 55-45 vote). He, too, served his full four-year term, finishing a couple of years into the Biden Administration. Beach had previously served in the conservative Heritage Foundation, on Republican Senate Budget committee staff, and at the libertarian Mercatus Center.

Beach’s tenure was marked by substantial data collection challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic. The accuracy of the first employment estimates were markedly volatile. Still, as with Groshen and Wiatrowski before him, Beach’s tenure saw the average first estimate too low by 0.01 percent. (Throwing out the March and April 2020 COVID-affected estimates, the average was low by 0.02 percent.)

However, from March 2022 to March 2023, the last year of Beach’s term, the first estimates were consistently too high. This was also true of Wiatrowski’s second stint as acting commissioner, from March 2023 to January 2024. During the last 13 months of Beach’s term, the first employment estimate was too high by 0.04 percent, on average, and it was high by an average of 0.05 percent for the 10 months of Wiatrowski’s term.

That brings us to McEntarfer, who was nominated by President Biden in July 2023 and confirmed in a vote of 86-8 by the Senate in late January 2024. McEntarfer previously had worked in the Census Bureau and served in the Obama Treasury Department and on Biden’s Council of Economic Advisers. Over the 17 months from February 2024 to June 2025, the first employment estimates were too high by an average of 0.04 percent—just as in the latter months of the Beach term and slightly lower than during the interim Wiatrowski term.

If the June estimate stays where it is in the next revision, it would be the biggest non-holiday, non-COVID downward revision going back at least to the start of 2013. (There were comparable or larger upward revisions three times in 2021, though they were likely related to data collection problems during the pandemic too.) It’s worth remembering that the June employment estimate could be revised upward next month, which would make the accuracy of the first estimate less of an outlier.

Moreover, the first May estimate was not an outlier in terms of how much it ultimately overstated employment. The revision of the March estimate was even larger, as were five revisions covering May 2023 to May 2024, with only the last two occurring on McEntarfer’s watch. The other three took place under Wiatrowski during the Biden presidency. (With McEntarfer gone, by the way, Wiatrowski is once again acting commissioner.)

Trump’s Truth Social post accused BLS of overstating jobs growth “right before the 2024 Presidential Election, in August and September.” He’s referring to the jobs report released on November 1, four days before Americans went to the polls, which revised job growth downward in those two months by a combined 112,000. Though Trump claimed this was a record, the downward revision in March was 167,000, and the July downward revision was nearly as high at 111,000. There were four downward revisions exceeding 100,000 in 2023.

The New York Times headlined its feature on the new August and September numbers, “U.S. Job Growth Stalls in Days Before Vote”—evidence, if it were needed, for the obvious conclusion that the revision was hardly a boon for the Kamala Harris campaign. And the same BLS report indicated that October had seen a pathetic 12,000 jobs added. Meanwhile, the first post-election jobs report found a gain of 227,000 jobs in November and revised upwards the September and October gains. If someone should have been fired for incompetence, it should have been whoever was supposedly in charge of getting Harris elected.

It’s not even clear what about the most recent jobs numbers Trump thinks is wrong. The White House memo criticizing McEntarfer implied that BLS had reported out overly optimistic job numbers back in July so that the Federal Reserve Board’s Federal Open Market Committee could justify higher interest rates. But the White House trumpeted these overly optimistic numbers when they came out. Are we to believe that if the May and June reports had accurately indicated job gains of only 19,000 and 14,000 (as the revised estimates show), that the July report with the meager 73,000 increase would have been OK?

Would McEntarfer even have lasted to the July report’s release? I mean, the May and June gains would have been the smallest since the pandemic—except for the tiny October gain reported right before the 2024 election…in order to…elect Kamala Harris. Am I getting this right?

Or perhaps Trump wishes BLS hadn’t revised the May and June numbers at all. But even in that case, the mediocre July number would have remained. Rather than reporting out an increase of 73,000 jobs in July, McEntarfer would have announced that jobs declined by 185,000. You have to go back to the earliest days of the pandemic to find anything remotely as bad as that. Here, too, it’s hard to see how McEntarfer would have kept her job.

What’s Gone Wrong with the Monthly Revisions?

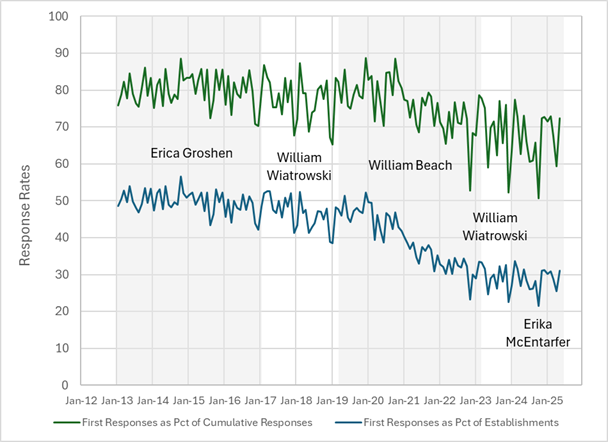

Here’s the simple answer to that question in one chart. Figure 2 shows the rates at which establishments have cooperated with BLS as it administers the CES. The upper line displays establishments who responded in time for the release of the first employment estimate as a share of establishments who responded in time for the release of the third estimate. Response rates fell notably during 2020, 2021, and 2022 and have remained low since. Rather than around 80 percent of establishments that eventually report employment numbers to BLS doing so in time for the first estimate, today it’s more like 65 percent. Apparently, establishments with relatively weak job growth became increasingly likely to report their estimates late. First estimates deriving from on-time reporters therefore tend to paint too rosy a picture of the economy. Revisions that incorporate laggard employers give a more accurate but gloomier impression.

Figure 2. Response Rates to the Establishment Survey, by BLS Commissioner Term

Note: Estimates from the Bureau of Labor Statistics Current Employment Statistics program (https://data.bls.gov/series-report?redirect=true, Series CEU00000000C1, CEU00000000C3, and CEU00000000RR). The upper line is estimated as the first preliminary release collection rate divided by the final sample-based release collection rate. The lower line is estimated as the first preliminary release responders divided by establishments selected for the CES sample. Computationally, it is the first preliminary release collection rate multiplied by (final response rate + (final response rate * (1 – final sample-based release collection rate) / final sample-based release collection rate)).

In an important regard, these estimates understate the response rate problem, because a substantial share of employers never gets back to BLS. (In most states, participation is voluntary.) The lower line in Figure 2 shows establishments reporting in time to be included in the first estimates as a share of all employers contacted for the CES. Rather than about half of establishments participating, as was the case a decade ago, today just 25 to 30 percent do. That raises the concern that since only a minority of employers are cooperating, they may not reflect broader employment trends as well as in the past.

The Benchmark Revision

That brings us to the third main revision to the CES employment estimates—the annual “benchmark revision.” Each year, as better data come in from other sources, BLS updates its March employment estimate. It then propagates the revision backward and forward in time, publishing the new results on Jobs Day the following February. Again, this is a regular, planned revision, not any indication an error has been made.

Trump’s allusions to an 818,000-job correction in 2024 relate to the benchmark revision that was preliminarily estimated in August of that year. BLS publicly released their “preliminary benchmark announcement” as in previous years, which they do once the data behind the new March estimate first become available. Those new figures indicated that nonfarm employment in March 2024 was lower by 818,000 than the CES had estimated. When compared with the previously-benchmark-corrected March 2023 employment estimates, the implication was that growth in employment over those 12 months was lower by that same amount.

Trump and other McEntarfer critics have suggested that this revision, too, was a political one on behalf of the Democratic Party. However, the BLS announcement came the day before Harris formally secured the nomination to be the Democrats’ candidate for president—literally the last day before the general election campaign. Why this would be good for Democrats is…not obviously apparent.

Indeed, the clear political liability it constituted was best expressed (if unscrupulously and irresponsibly) at the time by one Donald Trump, who posted on Truth Social,

MASSIVE SCANDAL! The Harris-Biden Administration has been caught fraudulently manipulating Job Statistics to hide the true extent of the Economic Ruin they have inflicted upon America. New Data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics shows that the Administration PADDED THE NUMBERS with an extra 818,000 Jobs that DO NOT EXIST, AND NEVER DID.

Perhaps the nonsensical logic of claiming BLS’s timing helped Harris is why Trump has…revised…the history of when the release occurred. In one of those Truth Social posts from the day he fired McEntarfer, he wrote:

Just like when [Democrats] had three great days around the 2024 Presidential Election, and then, those numbers were “taken away” on November 15, 2024, right after the Election, when the Jobs Numbers were massively revised DOWNWARD, making a correction of over 818,000 Jobs — A TOTAL SCAM.

The November 15 date suggesting a quiet post-election revision appears to be completely made of out of whole cloth. What really happened is that on the eve of the general election, a full two-and-a-half months from Voting Day, BLS made a routine announcement that happened to show that the economy had been even worse under the Democratic Party than voters thought.

It gets even better, though, because as it happens, Trump’s talking points are not just temporally challenged but out-of-date. In February 2025, when the benchmark analyses were complete, BLS reported that the actual March 2024 revision was 589,000. If there was a conspiracy to elect Kamala Harris, the downgrade of the miss from 818,000 to 589,000 sure could have been timed better.

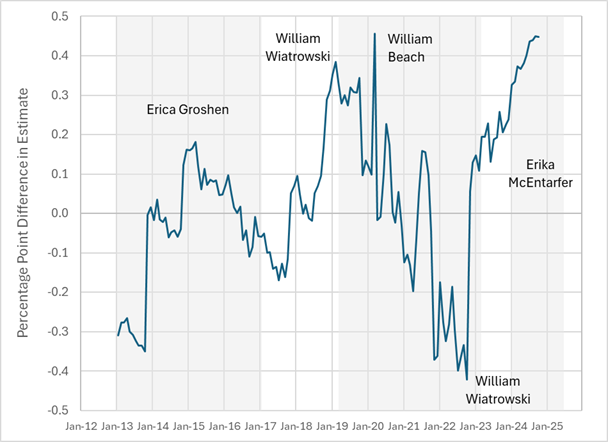

In Figure 3, I compare the third estimates (before any benchmark revision) to what they are today. The jumps apparent in these figures require some additional explanation for context. The estimates for most months (all except January, February, and March) are subject to two benchmark revisions. Each published revision in February begins with March of the previous year. Those revisions then are propagated back 11 months from March and forward through the just-past December.

So an employment estimate for, say, October 2023 was subject to a benchmark revision published in February 2024 (which updated the March 2023 employment estimate, previous ones through April 2022, and subsequent ones through the rest of 2023). Then it was also modified by the benchmark revision published in February 2025 (which updated the March 2024 estimate, previous ones through April 2023, and subsequent ones through the rest of 2024). Seasonally adjusted estimates may also change for up to five years, because the model for this adjustment is updated with each benchmark revision and applied to past years.

Figure 3. Percentage by Which the Third Nonfarm Employment Estimate was Off, Relative to Benchmark Revisions, by BLS Commissioner Term

(Positive = First Estimate too High, All Estimates Seasonally Adjusted)

Note: Estimates from the Federal Reserve Board of St. Louis (https://alfred.stlouisfed.org/series/downloaddata?seid=PAYEMS). All of the estimates are seasonally adjusted. The estimates compare the final sample-based estimates to the estimates as of Jobs Day, August 1, 2025. Chart runs to October 2024, since the November and December 2024 third estimates incorporate the initial benchmark revision applied to them and 2025 estimates have yet to be subject to a benchmark revision. The 2025 benchmark revision, which will be published in February 2026, will modify the April-October 2024 estimates shown in this chart (as well as the November and December 2024 estimates omitted).

Each year, the revision lifts or lowers 21 months’ of data together, causing jumps between years. Jumps show up systematically in Figure 3 between October and November. That’s because the third estimates for November and December already incorporate the benchmark revisions published in February. The third employment estimate for any November is the initial post-benchmark estimate. The only reason Figure 3 shows anything other than zeroes each November is that the November estimate may be revised by the subsequent benchmark revision (and by changes in seasonal adjustment). Meanwhile, the second estimate for any December is identical to the initial post-benchmark estimate, while the third estimate will differ because of new reporting from laggard establishments. It will then be revised again by the subsequent benchmarking.

It’s clear that the benchmark revisions have a bigger impact on the employment estimates than the one- and two-month-out revisions do. Still, the third estimates are generally off by less than one half of one percent. As noted, the third estimates for 2024 were too high relative to the benchmark estimates. But that was also true in 2015, 2018, 2019, 2020, and 2023, as well as during much of 2016. The third estimates have been too high since November 2022, and getting worse. That’s a trend predating McEntarfer’s term though.

Last year’s benchmark revision was unusually large. The downward revision to the March estimate (from which the adjustments to other months are propagated) was larger in 2024 than in any year since 2009, 15 years earlier, and you have to go back another 18 years before that benchmark revision, in 1991, until the 2024 revision is exceeded again.

But Figure 3 shows that the cumulative effect of revisions was not off the charts relative to recent experience. One reason the absolute revision is so much larger than in the past is that the labor market is larger than in the past, so a given percentage miss is larger today. Moreover, the effects of any one benchmark revision can be moderated (or exacerbated) by the subsequent, second benchmark revision. The third estimates from January to October 2019 were too high relative to the final ones by an average of 0.32 percentage points, while those from January to October 2024 were too high by 0.40 points. Nor was the year-to-year jump an unusual departure from recent history. The swing from the 2022 revision, which raised employment estimates that had been too low, to the 2023 revision, which lowered estimates that had been too high, is much more striking.

It’s worth remembering that the April-December 2024 estimates will be modified by the 2025 benchmark revision, which will be published next February. That revision will also modify the contentious May, June, and July figures for this year. In the meantime, we will get the preliminary estimate of the 2025 benchmark revision on September 9.

Concluding Outrage

The idea that Erika McEntarfer was fired for cause does not stand up. It is clear that she was dismissed not because of any operational breaches of protocol or because she is objectively doing a worse job at the challenging task of collecting timely and accurate employment data. That challenge has grown and has become more of a problem. But replacing the commissioner won’t fix it. It’s a problem that started well before McEntarfer’s term began. Fixing it will require giving BLS more resources to develop new solutions to the difficulties presented by low survey nonresponse.

An American president has removed the person running a statistical agency because he did not like the numbers it was producing. He has accused the agency of “rigging” official statistics, without any credible evidence. He clearly hopes to find someone who will deliver not the accurate numbers necessary for businesses, policymakers, savers, investors, students, and parents to make informed decisions, but the numbers that will flatter him and get him his preferred policies. Everyone else be damned. If that doesn’t upset you, you may not be as much of a patriot as you imagine yourself to be.