As President Donald Trump begins his second term, he and his administration will be exploring ways to improve government efficiency and economic outcomes for low-income Americans. One such policy—a 2019 regulation governing states’ use of waivers to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program’s (SNAP) work requirement—does just that. Although the regulation was never implemented after being challenged in court and later reversed by the Biden administration, our recent research finds that this regulation would improve the policy’s effectiveness and better target government resources.

SNAP is one of the United States’ largest transfer programs, providing almost $100 billion in benefits to low-income households each year. Like some other safety net programs, SNAP has a work requirement, meaning that certain recipients are expected to work or engage in training activities in order to receive benefits. In SNAP, all able-bodied adult recipients between the ages of 18 and 54 who do not have dependent children in their household (a group known as “able-bodied adults without dependents” or ABAWDs) are expected to work or volunteer for at least 20 hours per week in order to receive benefits. This policy covers approximately 15 percent of SNAP adults.

However, the US Department of Agriculture (USDA)—the federal agency that administers SNAP—allows states to waive the ABAWD work requirement if economic conditions in their state are poor. To qualify for a waiver, states are required to submit a request to the USDA, demonstrating that their state (or any area(s) within their state) has an unemployment rate above 10 percent or otherwise lacks a sufficient number of jobs. A lack of sufficient jobs is defined by USDA regulations and requires meeting at least one of six criteria:

- The area is designated as a Labor Surplus Area (LSA) by the Department of Labor,

- The area qualifies for Extended Unemployment Benefits,

- The area has a low and declining employment-to-population ratio,

- The area has a lack of jobs in declining occupations or industries,

- The area is described in an academic study as an area where there are a lack of jobs, or

- The area has a two-year average unemployment rate that is greater than 120 percent of the national average over the same two-year period.

Additionally, states are allowed to apply for waivers for any geographic unit of their choosing, and more importantly, are allowed to combine contiguous areas for the purposes of maximizing their waiver coverage. Therefore, even if one area (county, city, town, etc.) is not eligible for a waiver according to any of the above criteria, the area may still be able to receive a waiver if, when combined with contiguous areas, it is eligible as part of the combined area.

States have been able to use the USDA’s eligibility criteria—along with their ability to combine contiguous areas—to waive a significant number of ABAWDs in their state, even when economic conditions are strong. One common strategy is to combine a large number of counties into single area, and waive them under criterion (6). That criterion allows states to waive any area that has an unemployment rate at least 120 percent of the national unemployment rate—even when the national unemployment rate is low. For instance, in 2019, California was able to waive 52 of its 58 counties because, when combined, those 52 counties had an unemployment rate of 5.5, which was greater than 120 percent of the national unemployment rate over the same period (4.6 percent).

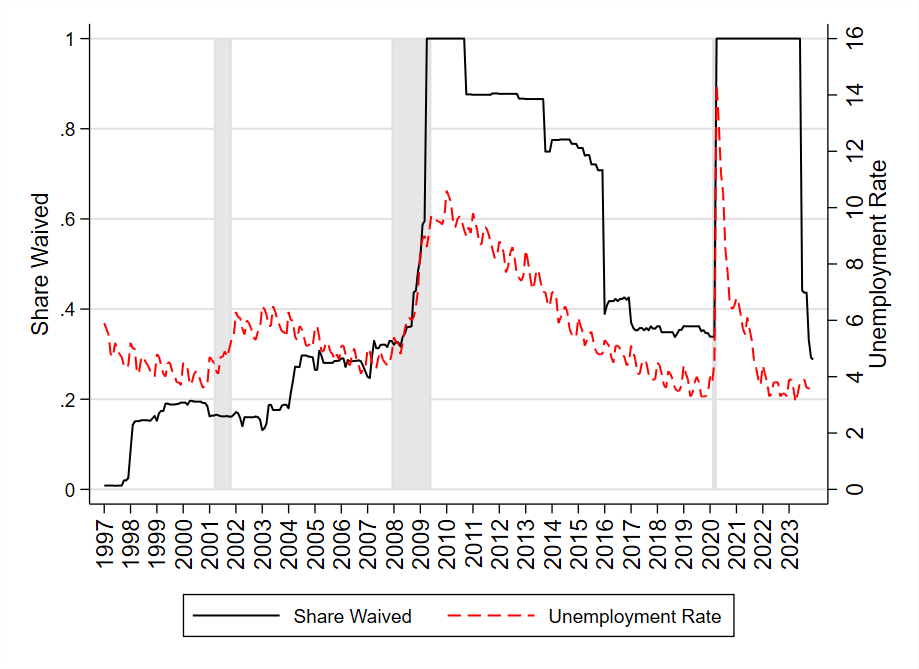

Although it is unclear how many states exploit the waiver eligibility criteria in this way, our research found that waiver coverage has increased over time. Figure 1 shows just how common waivers have become, and how waiver coverage does not always track the national unemployment rate. The black line, corresponding to the left axis, tracks the share of (population-weighted) counties eligible for a waiver, while the red line, corresponding with the right axis, displays the US unemployment rate.

Figure 1. Population-weighted share of US Counties with work requirement waiver, and national unemployment rate, monthly, January 1997-December 2023.

Notes: Figure reports share of population-weighted counties in the United States with a work requirement waiver in a given month. Grey shaded areas indicate recessions as defined by the National Bureau of Economic Research. All counties are counted as waived during federal waiver periods, even though it is possible that certain counties did not implement waivers during those times. Source: Richard V. Burkhauser, Kevin Corinth, Thomas O’Rourke, and Angela Rachidi, “Coverage, Counter-Cyclicality and Targeting of Work Requirement Waivers in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program,” Working Paper No. 33316 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2024), https://www.nber.org/papers/w33316.

Although waivers were less common in the early 2000s—likely due to implementation issues and limited enforcement of the work requirement to begin with—they became much more common following the Great Recession. From that point forward, waiver coverage remained high—oftentimes covering more than 75 percent of the population, even as economic conditions improved throughout the country.

In response to states’ use of waivers even when employment conditions were strong, the first Trump Administration proposed and finalized a rule in 2019 tightening the criteria by which a state could receive a waiver. The rule still offered waiver eligibility to areas with unemployment rates greater than 10 percent, but it would have changed the criteria by which an area could qualify under the “lack of sufficient” jobs condition. In general, states would only be allowed to demonstrate a lack of sufficient jobs if the area had an unemployment rate greater than 120 percent of the national average and greater than six percent. Additionally, the regulation only permitted waivers for individual Labor Market Areas (LMAs), disallowing states from grouping contiguous areas.

The most notable changes in the 2019 rule would have:

- disallowed states to qualify for waivers using Extended Unemployment Benefits eligibility;

- disallowed states to group contiguous areas under a single waiver justification;

- made areas with an unemployment rate below 6 percent ineligible for a waiver; and

- required states to use Labor Market Areas as the geographic unit for a waiver.

In a recent NBER working paper, we evaluated this proposed rule, assessing how each of the above changes would affect waiver eligibility levels, waivers’ responsiveness to changes in the local unemployment rate, and the degree to which waivers target the highest-unemployment areas.

To begin, we evaluated how the 2019 rule, if implemented, would have affected waiver eligibility. By relying on data from a variety of different sources—county-level unemployment data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, notices of Extended Unemployment Benefit eligibility, and guidance from the USDA—we simulated how widespread waiver eligibility is under current policy and under the 2019 rule. We found that if the 2019 rule were implemented, it would greatly reduce eligibility for waivers. Under the current policy, roughly 60 percent of (population-weighted) counties were eligible for a waiver in the average month from 1997 to 2023. However, if the 2019 rule had been in place during that time, just 17 percent would have been eligible for a waiver.

Figure 2 shows how waiver coverage would have been affected for each US county in December 2023, when the national unemployment rate was near an historic low of 3.5 percent. For each US county, the map reports whether the county was eligible for a waiver under existing policy and the 2019 rule. It also reports each county’s unemployment rate.

Figure 2. US Counties Eligible for Waiver Under Current Policy and 2019 Rule, December 2023.

Note: Figure displays county-level waiver eligibility for SNAP’s ABAWD work requirement in December 2023. Maps are shown separately for current policy and the 2019 Rule. Light-blue counties are ineligible for a waiver, while dark-blue counties are eligible for a waiver. The 2019 rule would have disallowed states from qualifying for a waiver due to Extended Unemployment Benefit eligibility, disallowed states from grouping contiguous areas, disallowed states from waiving any area with an unemployment rate below 6 percent, and required states to use the Labor Market Area as the geographic unit for a waiver. Source: Authors’ calculations, based on data from Richard V. Burkhauser, Kevin Corinth, Thomas O’Rourke, and Angela Rachidi, “Coverage, Counter-Cyclicality and Targeting of Work Requirement Waivers in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program,” Working Paper No. 33316 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2024), https://www.nber.org/papers/w33316.

Under existing policy, 1,191 counties were eligible for a waiver in December 2023. Together, those counties covered 29 percent of the US population, and had an average unemployment rate of 4.4 percent. However, if the 2019 rule were in place, just 190 counties would have been eligible for a waiver, covering just 10 percent of the US population. Those 190 counties, for comparison, had an average unemployment rate of 5.4 percent.

Waivers would also be more responsive to changes in the unemployment rate over time under the 2019 rule. Under existing policy, a one-percentage-point increase in a county’s unemployment rate corresponds with a 2.9 percentage point increase in waiver eligibility. However, under the 2019 rule, the same one-percentage-point increase in the unemployment rate corresponds with an 8.1 percentage point increase in waiver eligibility—a response nearly three times as large.

Additionally, the 2019 rule would better target waivers to the highest-unemployment areas. Under current policy, states are able to waive both low- and high-unemployment areas by grouping them together, whereas under the 2019 rule, only areas that themselves have high unemployment rates could receive waivers. According to existing policy, 32 percent of waiver-eligible counties (from 1997-2023) had unemployment rates below 5 percent. If the 2019 rule had been in place over the same period, just 11 percent of waiver-eligible counties would have had an unemployment rate below 5 percent.

Altogether, these reforms would help ensure that SNAP’s work requirement applies to those who are able to work and find jobs. Specifically, the 2019 regulation would reduce waiver coverage, but would make waivers more responsive to changes in the business cycle and better target truly disadvantaged areas. Together, these reforms strike a balance between preserving a safety net for the most vulnerable and encouraging broader workforce participation. As the Trump administration considers strategies to enhance government efficiency and economic opportunity, implementing these changes would represent a meaningful commitment to improving outcomes for low-income Americans and the broader economy.