After decades of industrial robots, factory layoffs, and outsourcing, automation has finally arrived in the cubicle. A recent Wall Street Journal article spotlighted how the new “robots for the mind”—the complex algorithms and language models of generative AI—are creating rising uncertainty in the professional class.

In the past, automation has generally been more of a concern for blue-collar workers, especially those in the manufacturing sector. However, multiple recent studies suggest generative AI, with its emphasis on language tasks, means some of the work done by people who make their living with words (whether writing, coding, or coordinating people) may find an AI at their elbow helping them do their jobs better and faster.

One of the conundrums of AI, however, is that unlike prior rounds of automation, workers with higher levels of education and skill are often more exposed than those with lower levels of knowledge and training. This doesn’t necessarily mean the value of lower-skill work is going up, but rather that higher-level skills are becoming more “democratized”—thereby allowing workers to do more complex tasks and jobs with fewer years of expensive education and training.

The Wall Street Journal article documents recent layoffs attributed to the adoption of generative AI. Even as the overall number of jobs lost remains low in absolute terms, it highlights a level unease among workers who increasingly see their jobs as potentially at-risk.

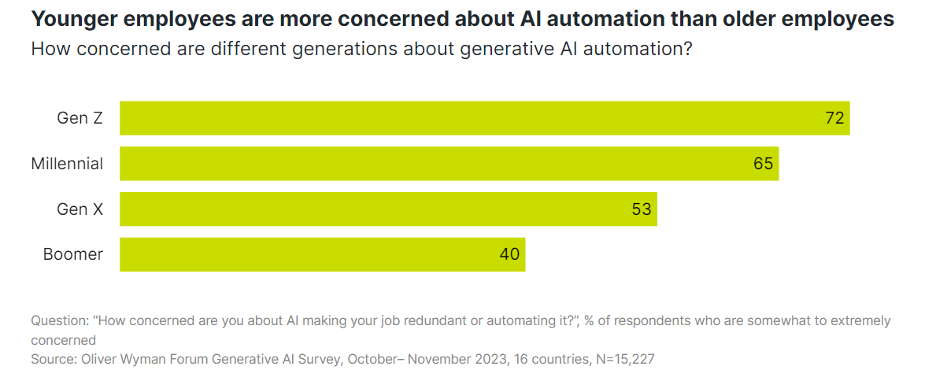

An Oliver Wyman Fund survey cited in the article documents broad concerns among workers about generative AI-enabled automation. Younger workers are most anxious: 65 percent of millennials and 72 percent of “Gen Zs” reported being somewhat to extremely concerned that AI will make their job redundant or that it will be automated. But older workers are concerned too: More than half of “Gen Xs” and a full 40 percent of “Boomers” report significant levels of concern.

Unease is natural, even warranted, but we should be careful to recognize that, for workers, it’s not all doom and gloom.

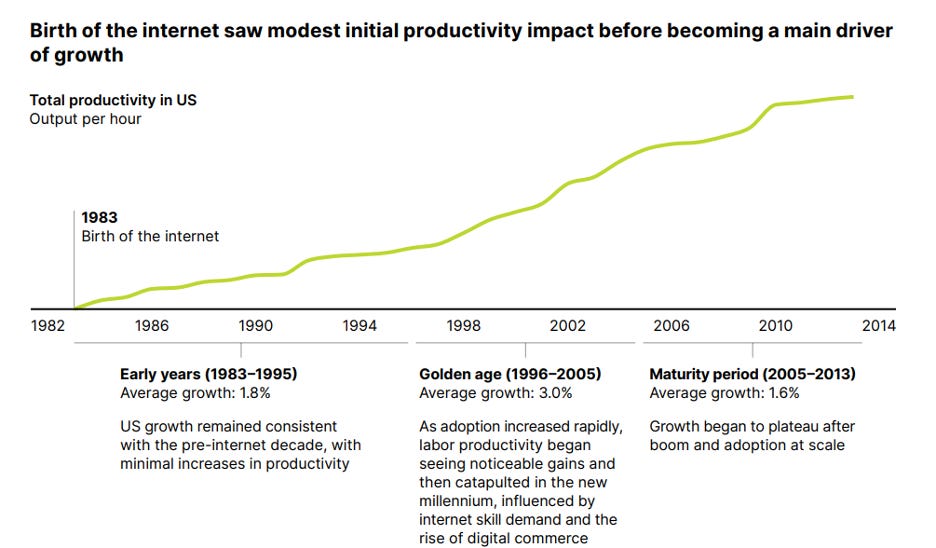

As the Wyman authors note, AI adoption is not a smooth, linear process. In theory, AI can do many things, but to produce significant productivity increases businesses must rethink and restructure their business process, a difficult and costly proposition in multiple dimensions. Businesses will face tough decisions about whether and how to incorporate AI given factors such as capital investments, burdensome trial and error, opportunity costs, and time and money spent retraining of workers. As the chart below shows, today’s ubiquitous, internet-powered economy didn’t appear overnight. It took four decades to get us to where we are, and 20 years before we realized large productivity gains.

The main certainties about AI and jobs are two-fold. First, the effects over time will be significant; and second, what those effects turn out to be is highly uncertain. In a forthcoming report, we look at the past 15 years of studies projecting AI’s impacts on jobs and skills. What we find is an abundance of contradiction leading mostly to questions rather than answers. For every paper forecasting risks of “replacement” and job loss, another anticipates job creation and “augmentation”—technology’s propensity to assist humans and boost their productivity rather than simply substitute for human labor. (This brings to mind the old joke of what would happen if we laid all the economists end to end. Answer: Nothing, because they never reach a conclusion anyway.)

Given this uncertainty, how can we prepare? The answer is simple, but not easy. As president and D-Day architect Dwight Eisenhower said, “plans are useless, but planning is indispensable.” He meant that plans are brittle and rarely withstand contact with reality. (Conveying the same idea somewhat more pithily, boxer Mike Tyson said, “Everyone’s got a plan until they get punched in the mouth.”) Planning, on the other hand, builds in self-knowledge, flexibility, and the capacity for adaptation to changing circumstances.

In the context of work and career, planning for uncertainty might take the form of paying greater attention to and investing in broad skill sets that give workers a diversified “portfolio” of capacities. When technology suddenly supplants a cherished, highly developed skill, the worker then has the cognitive flexibility, confidence, subject matter background, and social competencies required for adaptation and, if necessary, reinvention.

The foundation of the skills portfolio should be noncognitive or soft skills—such as flexibility, time management, teamwork, and communication. Taken together, these are the skills required for learning and allow workers assimilate and apply new knowledge in real-time. A recent IBM survey of 3,000 C-suite leaders across 28 countries found that in the past seven years, the soft-skills cluster has risen to the top of the “critical skills” list while proficiency in STEM and basic computer and software skills have dropped to the bottom.

That’s an important market signal. We should pay attention to it.

It is crucial not to lose sight of background uncertainty when tracking the latest developments in AI and employment. Layoffs are a fact of life in a market economy, and job losses among some high-skilled workers does not mean that a student should quit their computer science major because it is no longer safe.

The reality is, and has been for some time, there is nothing “safe” while the winds of “creative destruction” blow. The best solution is to start planning to be flexible.

Read the full article here.