The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated that the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) will reduce federal spending for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) by $186.7 billion over the next 10 years. SNAP is the country’s main food assistance program for low-income households, providing nearly $100 billion per year to help purchase groceries. On average, the OBBBA reduces SNAP spending by 16 percent annually compared to the CBO’s 2025 baseline.

While these reductions are substantial, they require important context. Unlike many recent headlines claim, most SNAP recipients will not experience any direct benefit cuts resulting from OBBBA’s spending reductions. Furthermore, claimsmade by The New York Times and others that grocers will close due to SNAP cuts or that states will stop administering the program because of the OBBBA are significantly overstated.

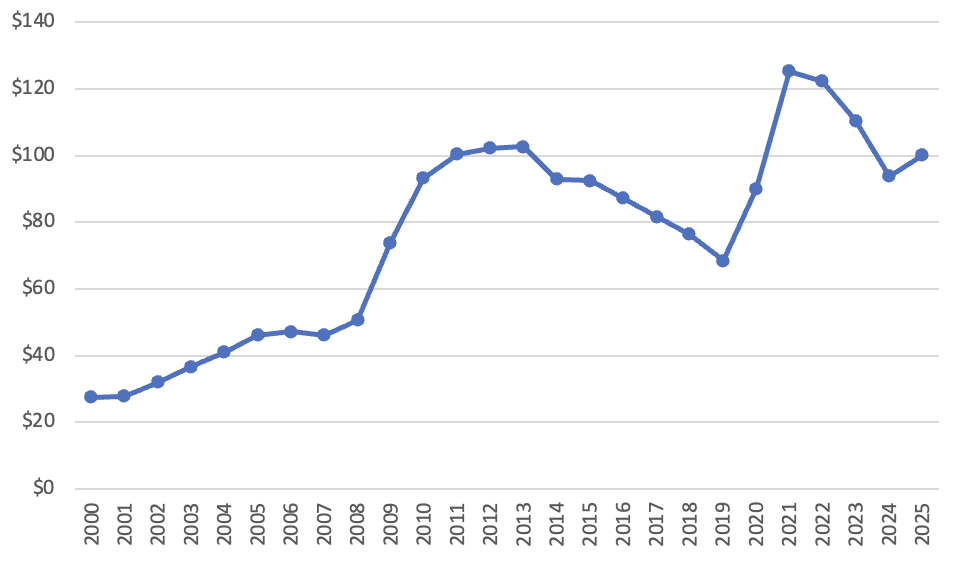

Before turning to specifics, it is important to note that even after the OBBBA’s spending reductions, SNAP’s average annual federal benefit costs—adjusted for inflation—will remain above pre-pandemic levels and will far exceed total benefit costs from the early 2000s (Figure 1). In fact, SNAP’s total expenditures (including administrative and other costs) in constant dollars are nearly double in 2025 compared to before the Great Recession in 2007. Put simply, the number of households receiving SNAP and total expenditures has grown dramatically over the past two decades.

Figure 1: Total SNAP Federal Benefit Costs ($2024)

Source: US Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service SNAP Expenditures.

SNAP’s growth has far outpaced what population increases, the economy, and unemployment rates would predict. In a March 2025 report, Thomas O’Rourke and I showed that even after adjusting for population changes, SNAP expenditures in recent years are roughly three times higher than what changes in the unemployment rate alone would predict. SNAP caseloads have expanded far beyond what economic conditions alone would justify and remain at levels much higher than years past.

The OBBBA’s SNAP cuts should also be viewed in the broader context of federal and state spending. Approximately 35 percent of SNAP’s federal spending reduction comes from the OBBBA shifting benefit costs and some administrative costs to the states (see details below). States will either cover these new costs or forego hundreds of millions in federal SNAP dollars. Assuming states absorb these costs, the impact on SNAP participants and benefit levels will likely be minimal.

The following outlines the specific SNAP changes authorized by the OBBBA, along with their 10-year estimated budget impact and the context behind each provision. A summary is provided in Table 1.

1. The OBBBA ends the Food and Nutrition Service’s (FNS) ability to administratively raise SNAP benefit levels without Congressional input – $37 billion reduction. The OBBBA stops the practice of the FNS using a routine reevaluation of the Thrifty Food Plan to administratively increase SNAP benefit levels. The CBO estimates that ending this practice will account for approximately 20 percent of the total SNAP spending reduction. Importantly, according to the CBO, this reform has no anticipated effect on participation and it will not cut current benefits for any SNAP recipients. Instead, ending this practice prevents future benefit increases driven by administrative discretion and restores the Thrifty Food Plan’s historical cost-neutral standard—that is, it still mandates routine cost-of-living adjustments. Absent this reform, any future Presidential administration could unilaterally increase SNAP benefit levels, circumventing the oversight and authority of Congressional appropriators.

Context: As I have covered before, in 2021 President Biden’s FNS took unprecedented action to increase SNAP benefit levels administratively through a questionable reevaluation of the Thrifty Food Plan. Prior to this action, only Congress had ever raised SNAP benefit levels, including a mandated adjustment each year for the cost of living. SNAP benefit levels have always been pegged to the Thrifty Food Plan, which reflects the cost of a budget conscious and nutritious diet. But in a clear case of executive overreach, President Biden’s FNS used a routine reevaluation of the Thrifty Food Plan in 2021 to raise SNAP benefit levels beyond inflation without the consent of Congress.

2. Enacts common-sense reforms to SNAP’s existing work requirements – $68 billion reduction. The OBBBA makes two important changes to SNAP’s existing work requirements, accounting for 37 percent of projected SNAP spending reductions over 10 years. The CBO estimated that approximately 3 million fewer individuals will participate in SNAP each year as a result of these changes. Notably, these estimates did not consider the potential positive income impacts of work requirements over the long term.

OBBBA’s work requirement changes involve: (1) ending states’ ability to waive the existing ABAWD work requirement unless the state or local area’s unemployment rate averages 10 percent or higher, and (2) expanding the definition of ABAWD by increasing the age to 65 (from 54), adding parents of children age 14 or older (previously parents were exempted), and ending the exception for homeless individuals, veterans, and youth who have aged out of foster care. Any noncontiguous state (i.e., Alaska and Hawaii) can still waive the ABAWD work requirement granted their unemployment rate is 1.5 times the national unemployment rate.

Based on the CBO’s assessment of the House version of the OBBBA (CBO has not assessed participation effects of the final OBBBA), the largest impact on participation (and likely the largest source of spending reductions) comes from tightening the criteria by which states can waive the existing ABAWD work requirement, resulting in a projected reduction of 1.4 million participants. Expanding the age to 65 had the next largest effect (1.0 million individuals), and adding the requirement to parents of children age 14 and older had the smallest impact (notably, the House version added the requirement to parents of children 7 and older). Importantly, under OBBBA, if a parent fails to meet the work requirement, only their pro-rated share of the SNAP benefit decreases – their children remain SNAP eligible.

Context: Since the 1996 welfare reform law, work-capable adults can only receive SNAP for three months in a three year period unless they work, volunteer, or participate in an approved employment program for 20 hours per week on average. Known as able-bodied adults without dependents (or ABAWDs), these individuals must document their employment or work-related activity to continue receiving SNAP. However, the 1996 law also gave states the ability to waive these requirements when the unemployment rate is above 10 percent or there is a lack of sufficient jobs for these individuals. As my co-authors and I have shown, USDA regulations on what constitutes insufficient jobs has allowed many counties to receive waivers despite favorable employment conditions. The OBBBA eliminates the insufficient job criteria and allows waivers only when an area demonstrates an unemployment rate of 10 percent or higher.

SNAP has well documented work disincentives, and work requirements can counteract those disincentives. Tightening the ABAWD waiver criteria and expanding the definition of ABAWDs will ensure that more individuals are encouraged to seek employment as an alternative to SNAP. Importantly, the expanded work requirements target only those deemed sufficiently able to work, exempting children, the elderly, the disabled, individuals with health limitations to work, caretakers of children under 14, and pregnant women.

3. Shifts benefit and administrative costs to states – $65 billion reduction. The OBBBA changes the financial architecture of SNAP by shifting the responsibility for some benefit costs and a larger share of administrative costs to states, accounting for 35 percent of the overall federal spending reduction. Prior to the OBBBA, the federal government covered 100 percent of benefit costs, and 50 percent of administrative costs. Now, states must contribute a share of benefit costs based on their payment error rates. If states maintain a payment error rate below 6 percent—a historical benchmark—they will owe nothing toward benefit costs. The final OBBBA included a delay in implementation of the matching requirement until October 1 2027, and added an accommodation for states with extremely high payment error rates, delaying implementation of the matching requirement until 2029 or 2030 for them. Administrative costs total approximately $11 billion per year, representing 11 percent of total program costs. Under OBBBA, states are required to cover 75 percent of administrative costs, up from the prior 50 percent, shifting roughly $2.7 billion per year to the states. The CBO’s estimated spending reductions incorporate an implementation delay for the administrative cost sharing provision until October 1 2026.

Context: There are two desired outcomes associated with shifting a share of benefit costs to states. First, it will incentivize states to reduce their payment error rates. Payment errors can have tremendous fiscal consequences for the federal government. Ensuring that states have a financial stake in reducing payment errors will reduce government waste. Furthermore, reducing payment errors are an achievable outcome based on historical precedent. In FY 2024, the average payment error rate across states was 10.93 percent, and 43 states or territories exceeded the 6 percent target. However, these high payment errors are a relatively new phenomenon. In FY 2019, the average payment error rate was 7.36 percent and 29 states exceeded the 6 percent target, while in FY 2013 the average payment error rate was 3.20 percent and only 3 states exceeded the 6 percent target.

Second, beyond incentivizing lower payment error rates, giving states a financial stake in the program encourages them to prioritize self-sufficiency over long-term government dependence for low-income households. For too long, SNAP has been framed primarily as an economic stimulus for local economies rather than as a pathway for households to escape poverty and expand opportunity. Shifting a larger share of administrative costs to states will create a positive incentive by encouraging administrative efficiency.

Claims that state officials may end SNAP in their state rather than contribute a small share toward benefit and administrative costs are far-fetched. Politico reported that Governor Shapiro of Pennsylvania said “I’m very worried about our ability to even keep the SNAP program going if the House or Senate bill ultimately becomes law.” Pennsylvania received $4.3 billion from the federal government through SNAP to help low-income Pennsylvanians afford food in FY 2024, while reporting a 10 percent payment error rate. Under the benefit and administrative cost shift, low-income Pennsylvania households would still receive $3.7 billion from the federal government for SNAP, with Pennsylvania covering an additional $600 million (10 percent of benefit costs, and an additional 25 percent of administrative costs). If Pennsylvania reduced their payment error rate and increased administrative efficiency, they could lower their share even more. The idea that the Governor of Pennsylvania would leave $3.7 billion of federal funding for low-income households on the table rather than reduce their payment error rate strains credibility.

More likely, states may choose to end their use of eligibility expansions, known as broad-based categorical eligibility that they have increasingly used in recent years. Broad-based categorical eligibility allows states to confer SNAP eligibility to households that qualify for other government benefits, such as the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), at income levels higher than SNAP’s statutory 130 percent of the federal poverty level. Ending this practice would be a welcome policy change because it would target assistance to those most in need. Even if states choose to end their program or reduce eligibility as a result of OBBBA’s passage, those decisions are appropriately left to state officials and the voters who hold them accountable.

4. Eliminates funding for SNAP-Education – $5.5 billion reduction. The OBBBA eliminates all federal funding for the SNAP nutrition education program, accounting for 3 percent of OBBBA’s overall federal SNAP spending reduction. The CBO estimates that this provision will reduce federal spending by $5.5 billion over 10 years and will have no effect on participation.

Context: SNAP is essentially a nutrition program and since the 1970s the federal government has funded nutrition education efforts targeting low-income households through the states. While SNAP-Education has some evidence of effectiveness, including that it improves knowledge and nutrition behaviors, research has been mixed. The central question, however, in assessing the place of nutrition education within SNAP is whether the program is redundant with other existing initiatives. Many other programs within the USDA operate nutrition education and the CDC is the nation’s primary public health prevention agency, focusing on preventing obesity and diet-related disease. The CDC already administers school nutrition programs, and other community health programs. In fact, because nutrition education programs operate across so many federal agencies, it is challenging to document the total amount spent by the federal government on these efforts. The OBBBA’s elimination of SNAP-Education will reduce redundancy and place the responsibility for population-based nutrition education with other USDA agencies, or the CDC.

5. Changes some SNAP eligibility factors, including eligibility for certain categories of non-citizens – $18.3 billion reduction. The OBBBA makes three key changes to SNAP eligibility and how benefit amounts are calculated, accounting for approximately 10 percent of SNAP’s federal spending reduction. First, it changes how utility expenses are documented for households without an elderly or disabled person. The CBO estimates that this change will reduce federal spending by $5.9 billion over 10 years. Second, it no longer allows internet expenses to count toward excess shelter costs, which will increase net income and modify SNAP benefit amounts downward. The CBO estimates that this will reduce spending by $10.9 billion over 10 years. Finally, while SNAP has long been limited to citizens and permanent residents in the country for more than 5 years, certain other categories of non-citizens had previously been eligible. The OBBBA removes SNAP eligibility for certain refugees and asylum seekers. The CBO estimates that this provision will reduce federal funding by $1.5 billion over 10 years.

Context: When calculating SNAP eligibility and benefit amounts, certain utility and internet expenses are deducted from gross income to achieve the net income estimate. Benefit amounts are then based on net income, which incorporates these deductions. The OBBBA limits the use of a standard utility allowance for households without an elderly or disabled person and no longer allows internet expenses to be considered for the excess shelter deduction. The net effect of these changes will be to raise net income and reduce SNAP benefits for affected households. According to CBO estimates, the utility allowance adjustment will impact just 3 percent of SNAP households, while the revised treatment of internet expenses will affect 65 percent of households, but with an average benefit reduction of only $10 per month.

Conclusion

The CBO estimates that the OBBBA will reduce overall SNAP spending by $186.7 billion over the next decade. These provisions rein in recent administrative benefit increases, reaffirm the principle of work over long-term government dependence, increase state accountability, and eliminate waste and redundancy. Contrary to claims in the press, these spending reductions will not uniformly cut current SNAP benefits, nor will they affect most SNAP participants in a meaningful way.

Table 1: Summary of OBBBA’s SNAP Provisions

| Provision in OBBBA | Description | CBO Spending Reduction over 10 years / Participation Effect | Effective Date |

| Sec 10101: Thrifty Food Plan | Ensures that any future reevaluations to the Thrifty Food Plan are cost neutral, meaning that the FNS must reevaluate the basket of goods within the cost constraints of the existing Thrifty Food Plan, adjusted for inflation. | -$37,300 million; no effect on participation. | Effective immediately. |

| Section 10102: Work Requirements | Modifies exceptions to SNAP recipients subject to the time limit rule. It maintains the current time limit – receipt in 3 months in 3 year period unless working, training or volunteering 80 hours per month.Increases age range to 18-65 (from 18-54).Adds parents of children age 14 and older to time limit group.Eliminates previous exceptions for homeless, veterans, and foster youth aging out (added in 2023).All other exceptions remain: pregnant women, disabled, Indian heritage. | -$68,600 million for all work requirement provisions (including changes to waivers). CBO estimated age expansion would reduce participation by 1.0 million adults and the parent requirement by 0.8 million, but that involved the House version (parents of children 7 and older). CBO did no estimate participation effects of the final OBBBA. | Effective immediately and upon new guidance from FNS. |

| Section 10102: Work Requirements – ABAWD Waivers | Strikes language that allows a waiver of the ABAWD time limit for areas that “did not have a sufficient number of jobs to provide employment for individuals”. Only areas with unemployment rates of 10 percent or higher are eligible for a waiver. Allows exemptions for noncontiguous states (Alaska and Hawaii) to apply for exemption if unemployment rate is 1.5 times the national average. | -$68,600 million for all work requirement provisions (including changes to waivers). CBO estimated that the waiver policy would reduce SNAP participation by 1.4 million adults. | Effective immediately upon new guidance from FNS. |

| Section 10103: Standard Utility and Section 10104: Internet Expenses | Does not allow internet service fees to be considered as part of excess shelter deduction. | -$5.9 million for SUA changes and -$10,980 billion for internet expenses change; CBO estimated 3% of households would experience $100 per month reduction due to SUA and $10 per month for 65% of household through internet expense. | Effective immediately upon new guidance from FNS. |

| Section 10105: State Error-Rate Cost Share | States pay up 0% of benefit costs when payment error rate is <6%. They pay 5% when payment error rate is 6- <8%, 10% when 8%-<10%, and 15% when payment error rate is >10%. | -$40,810 million; CBO estimated that the new match requirement would reduce participation by 1.3 million people (likely through elimination of BBCE). | October 1 2027; delayed even longer for states with extremely high payment error rates. |

| Section 10106: Admin Cost Share | Federal reimbursement for SNAP administration costs decreases from 50% to 25%,meaning states assume 75% of admin costs. | -$24,660 million; no effect on participation. | October 1, 2026 |

| Section 10107: SNAP‑Ed Funding Elimination | Ends federal grants for nutrition education. | -$5,470 million; no effect on participation. | October 1 2025 |

| Section 10108: Eligibility for Noncitizens | Restricts SNAP receipt to citizens, permanent residents and Haitian or Cuban entrants. Excludes refugees and asylum seekers. | -$1,904 million; 120,000 – 250,000 become ineligible. | Effective immediately upon new guidance from FNS. |

| Source: Public Law 119-21 https://www.congress.gov/bill/119th-congress/house-bill/1; CBO Estimated Budgetary Effects of Public Law 119-21, to Provide for Reconciliation Pursuant to Title II of H. Con. Res. 14, Relative to CBO’s January 2025 baseline, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/61570. | |||