Congress’s efforts to produce “one big, beautiful bill” that reflects President Donald Trump’s tax and spending priorities is about to kick into high gear as the House and Senate turn to crafting their respective reconciliation bills. Yet one key source of contention between House and Senate Republicans remains the amount of mandatory savings included in those coming bills. Senate Republicans adopted a target of just $4 billion in 10-year savings, which House Republicans reluctantly agreed to even as they insist on finding greater savings. (For context, $4 billion would constitute just 0.2 percent of the $1.8 trillion in mandatory federal spending in FY 2024 not counting Social Security and Medicare—and an even smaller share over the next decade.) Meanwhile, liberal opponents have already decried potential changes as “draconian cuts.” Those competing forces suggest a bumpy road ahead for Republicans hoping to rally around specific policies achieving significant budget savings, especially given their razor-thin congressional majorities. But they could reach their savings goals another way: by changing the federal/state financing structure and implementing block grants for SNAP and/or Medicaid. As discussed below, doing so offers important rhetorical and other advantages, promoting that “in case of emergency, open block grant” approach.

The following COSM Commentary is divided into two parts. Part 1 reviews the history of the TANF block grant, including savings federal taxpayers have experienced since its creation and responses to those who argue block grants undermine the “automatic stabilizer” nature of means-tested programs. Part 2 reviews several rhetorical advantages for policymakers of similarly converting other open-ended entitlement programs to block grants, and offers concluding thoughts.

Part 2: Rhetorical Advantages of Block Grants

The advantages block grants confer extend beyond federal savings. For example, for states block grants lock in predictable funding and are often accompanied by significant increases in state control over program operations. As the TANF experience shows, when caseload reductions follow, block grants can result in increased funds available per recipient and family even when the block grant itself remains fixed.

For federal policymakers seeking program savings, block grants also offer three significant rhetorical advantages over more specific spending cuts. These advantages may be especially compelling to current lawmakers seeking to identify program savings while rebutting charges they are “cutting benefits” or “cutting recipients.”

Advantage #1: Depending on program baselines or starting dates, a block grant can achieve savings while locking in stable or even growing federal funding, rebutting opponents’ “cutting spending” rhetoric.

Real savings can be achieved by replacing open-ended entitlements with fixed block grants in several ways. Especially for programs with rapidly growing baselines, block grants can set funding at stable or even growing levels while still achieving significant savings, persuasively rebutting opponents’ “cutting spending” rhetoric.

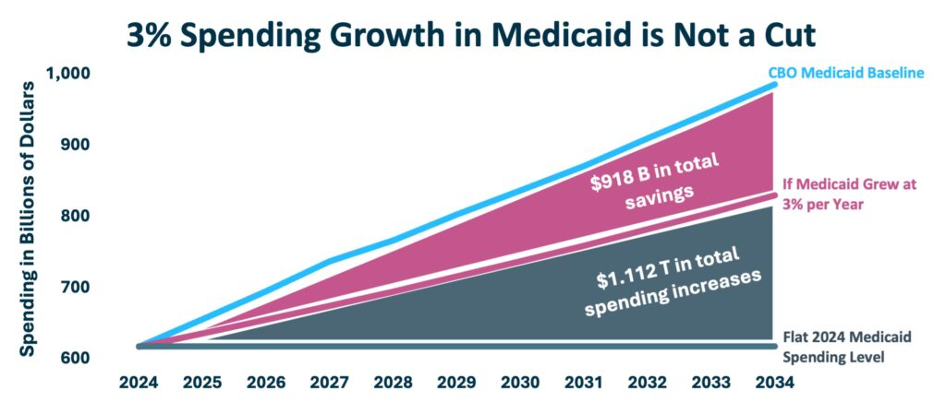

For example, the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office currently expects Medicaid spending to grow from $618 billion in 2024 to $986 billion in 2034. As the Economic Policy Innovation Center notes, if that current 5 percent annual growth rate were restrained (such as under a block grant) to 3 percent, spending would still rise in every year, reaching $830 billion in 2034, an increase of over $200 billion from the 2024 level. Yet as displayed in Figure 3, even as program spending grows by over $1.1 trillion across 10 years, savings of over $900 billion would result from slowing the program’s current rapid growth rate.

Figure 3. Medicaid Spending under Current Baseline and 3% Growth Option

Source: Economic Policy Innovation Center

Even programs with more stable baselines could achieve significant savings by converting to a block grant, depending on the starting point and other features. Consider SNAP. According to the same CBO baseline, SNAP spending is projected to grow from $110 billion in 2025 to $116 billion by 2034. However, those levels reflect the continuation of policy changes recorded during the pandemic, which through 2022 nearly doubled pre-pandemic spending and remain significantly elevated today. SNAP spending in FY 2019, that is, before pandemic caseload growth and the benefit increases enacted by President Biden’s administration, was $60.4 billion ($74 billion in current dollars). Converting the SNAP program into a block grant set at that pre-pandemic level (before pandemic expansions and the Thrifty Food Plan reevaluation) would achieve the goals of those seeking to end pandemic-era expansions now that the COVID-19 emergency is well past, as well as to reverse benefit increases made without Congressional input. Regardless of how the federal block grant is set (and adjusted, including for inflation), additional savings could be achieved by expecting states to contribute toward benefit costs, as recently proposed by Sen. Mike Lee (R-UT) in the SNAP Reform and Upward Mobility Act.

As these scenarios display, various block grant options can effectively challenge the narrative of opponents of more specific reforms by displaying how savings can be achieved by increasing federal funding at a more modest pace, or resetting program spending to pre-pandemic levels.

Advantage #2: Increased flexibility provided to states administering a block grant can help rebut opponents’ “cutting recipients” arguments.

Just as growing annual block grant funding can help rebut charges of cutting spending, the flexibility inherent in block grant programs can help repel charges of “cutting recipients,” or at least make those charges less salient or certain compared with alternative reforms.

Assume the federal government created a SNAP block grant tied to pre-pandemic SNAP funding that then grows with inflation while offering states more flexibility in determining benefit eligibility and other program terms. Opponents may charge such a change would necessarily cut the number of benefit recipients, since the average SNAP caseload in 2019 was 35.7 million, versus 41.7 million in 2024. But that charge would require adopting assumptions about state and individual decisions and behavior that may not bear out—or at least not be knowable in advance in a block grant setting.

For example, some states might respond to the new block grant by increasing their own state funding (whether required by federal policy or not) in order to maintain current benefits. Other states might alter some benefit payments—such as by reducing payments to working-age, able-bodied individuals with long benefit durations—while leaving the number of recipients unaffected. Still others might respond to the block grant by expanding work requirements or setting lifetime limits on benefits, resulting in fewer individuals remaining on or applying for SNAP benefits. It can reasonably be asked if more recipients and would-be claimants respond to such changing eligibility terms, which are widely supported by the public, by opting not to claim benefits, does that constitute “cutting recipients”?

Further, as seen with the TANF block grant, even if there are fewer claimants, that would result in more federal funds available per each remaining recipient. As a result, states might increase benefits for some, such as disabled individuals, or shift more resources to education and training programs designed to assist able-bodied adults in returning to work. In this way, block grants accompanied by more state flexibility could result in more benefits that better fulfill the mission of means-tested entitlement programs—that is, to help more in need better support themselves or their families. Unless a policymaker’s intent is to simply maintain more Americans on food stamps or other benefits, block grants can offer states a better way of achieving program goals, especially assisting those who cannot support themselves.

As with the TANF block grant, different states are likely to adopt different practices, making generalizations such as “the block grant will cut recipients” difficult if not impossible to substantiate. That is especially the case if supporters can point to growing federal (or a combination of federal and state) funds compared with current levels.

Advantage #3: States are better positioned to take on additional decision-making and funding responsibility, which block grants promote.

A fixed block grant will force states to take a hard look at current policies and seek efficiencies, obviating the need for often more controversial federal policy mandates such as repealing recent Biden benefit expansions. In effect, the block grant allows federal lawmakers to defer to state officials in determining the right policy mix needed to properly match federal funds with local needs. While Republican-led states (which in recent years opted to end federal pandemic unemployment benefits that discouraged returns to work) seem most likely to support policies resulting in smaller caseloads, the TANF experience suggests they would not be alone. TANF caseloads declined significantly in all states following the creation of the federal block grant. And while TANF savings vary widely among states, the Government Accountability Office recently reported that, across all states, “unspent TANF funds more than doubled to $9 billion from FY 2015-22.”

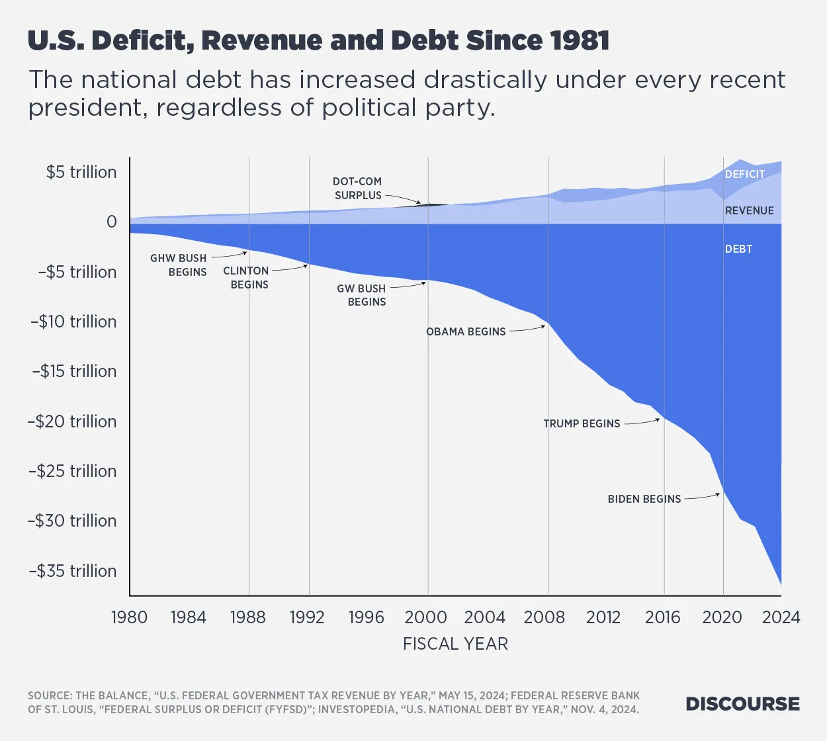

Another important factor backstops this entire debate—the increasingly dire federal budget situation. As Figure 4 displays, federal debt—and with it, interest payments that already exceed federal spending on children—continues to accelerate despite growing federal revenues.

Figure 4.

By comparison, State budgets are relatively flush, including due to record infusions of federal funds during the pandemic. For example, a recent fiscal survey of states suggests most states have growing rainy day funds:

The median rainy day fund balance as a percentage of general fund expenditures has grown every year since the aftermath of the Great Recession in fiscal 2011, and states are expecting to continue this streak, with a median balance projected at 14.4 percent at the end of fiscal 2025.

That fact, combined with the state experience with the TANF block grant, suggests states can take on not only more responsibility for the design of social programs but also their funding. Indeed, the federal government’s long-run fiscal outlook suggests policymakers may have no choice but to make the transition to greater state control and financial responsibility for these programs.

Concluding Thoughts

If Republican lawmakers struggle to agree on specific reforms designed to produce safety net program savings, the creation of the TANF block grant in the 1990s offers the example of an alternative approach for which support may be easier to rally. Indeed, many of the same arguments heard today against “draconian cuts” were voiced about the creation of the TANF block grant and associated welfare reforms. Yet contrary to the worst fears of liberal opponents, those reforms were followed by remarkable increases in work and earnings, matched by significant declines in poverty and dependence. Meanwhile, the creation of the fixed TANF block grant has saved federal taxpayers an estimated $178.6 billion simply by its remaining unadjusted for inflation since 1997. That unadjusted block grant continues to be regularly extended—almost always with bipartisan support—at its original 1997 level.

That history is more relevant than ever as Congress considers changes to open-ended entitlement programs designed to assist low-income individuals and families, including SNAP and Medicaid. In some ways, the budgets of those programs are remarkably worse than the pre-reform AFDC program. Both SNAP and Medicaid spend far more. Coverage admittedly varies, but in contrast with dramatically shrinking dependence on welfare checks over the past three decades, repeated eligibility expansions have increased the share of the US population on Medicaid from 11 percent in 1999 to 29 percent in 2023. Current SNAP receipt and spending also remain significantly elevated, especially compared with pre-pandemic levels.

Under these current open-ended entitlements, more federal funds flow into states whenever they fail to help Americans work and support themselves. In contrast with that perverse incentive, block grants can lock in historically high levels of federal funding while promoting efficiencies toward the goal of better helping recipients help themselves. With broader use of block grants, the federal government would maintain a strong oversight role, monitoring process and outcome metrics from the states, such as number of people served and number of people employed, as well as auditing state finances to ensure federal block grant dollars are spent in accordance with program goals. But the federal government would leave program design and implementation decisions to the individual states, where they more appropriately belong.

The TANF experience is instructive on all fronts. Despite the worst fears of opponents of reform, fixed federal TANF funding not only proved more than adequate to the reformed program’s goals, but increased work and declining dependence resulted in record federal funding per recipient and family on benefits, even to this day. Along the way, states devoted surplus funds to promoting more work, strengthening families, and saving for rainy days, while federal taxpayers achieved significant savings. Those and other reasons suggest that, if federal policymakers find they cannot agree on more specific reforms, they should consider the potential benefits of replacing current open-ended entitlements with similar block grants.