Congress’s efforts to produce “one big, beautiful bill” that reflects President Donald Trump’s tax and spending priorities is about to kick into high gear as the House and Senate turn to crafting their respective reconciliation bills. Yet one key source of contention between House and Senate Republicans remains the amount of mandatory savings included in those coming bills. Senate Republicans adopted a target of just $4 billion in 10-year savings, which House Republicans reluctantly agreed to even as they insist on finding greater savings. (For context, $4 billion would constitute just 0.2 percent of the $1.8 trillion in mandatory federal spending in FY 2024 not counting Social Security and Medicare—and an even smaller share over the next decade.) Meanwhile, liberal opponents have already decried potential changes as “draconian cuts.” Those competing forces suggest a bumpy road ahead for Republicans hoping to rally around specific policies achieving significant budget savings, especially given their razor-thin congressional majorities. But they could reach their savings goals another way: by changing the federal/state financing structure and implementing block grants for SNAP and/or Medicaid. As discussed below, doing so offers important rhetorical and other advantages, promoting that “in case of emergency, open block grant” approach.

The following COSM Commentary is divided into two parts. Part 1 reviews the history of the TANF block grant, including savings federal taxpayers have experienced since its creation and responses to those who argue block grants undermine the “automatic stabilizer” nature of means-tested programs. Part 2 reviews several rhetorical advantages for policymakers of similarly converting other open-ended entitlement programs to block grants, and offers concluding thoughts.

Part 1: The TANF Block Grant Example

What’s a block grant? The basic idea is the federal government distributes a fixed amount of funding each year to states, allowing them to decide how to spend it within certain guidelines around a social program or need. Some block grants require states to contribute their own funds, while others do not. Unless Congress provides emergency funding during recessions, federal block grants normally remain fixed at pre-set levels, sometimes without even an inflation adjustment and regardless of changes in the number of recipients or other factors. That contrasts sharply with open-ended entitlements, where federal funding automatically grows whenever more people qualify.

The most well-known block grant is the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) block grant, created over a generation ago as part of the 1996 welfare reform law. That bipartisan law, drafted by congressional Republicans and signed by President Bill Clinton, completely altered the welfare program’s financing structure. It ended the open-ended entitlement to federally funded welfare checks provided under the former Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) program and replaced it with the fixed TANF block grant. The new law established four broad goals for program funds, including providing assistance to needy families. The law set requirements for how states could provide assistance to adults, including work requirements and time limits. Beyond that, the block grant’s financing structure gave states broad flexibility to allocate funds as they saw fit, so long as the spending supported low-income families with children and aligned with the program’s goals.

The results were dramatic. First, welfare caseloads plunged even as Congress was crafting the new rules. Between fiscal years 1995 and 2000, the average annual US cash welfare caseload fell 54 percent from 13.5 million to 6.2 million recipients (which includes both children and adults). Alongside those changes were enormous strides in increasing work and earnings and reducing poverty, as one of us (Weidinger) noted on the 25th anniversary of the 1996 law:

After reform, welfare caseloads plummeted as millions of mothers left or stayed off the welfare rolls in favor of work. In just the five years after August 1996, the number of families on welfare dropped over 50 percent. Aided by a strong economy, the share of never-married mothers (the group most likely to go on welfare) who worked rose almost 40 percent over the four-year period beginning in 1996.

Child support grew and additional funds for childcare, extended health insurance, and tax credits that rewarded work all made going to work pay better than staying on welfare. As a result, earnings rose sharply while poverty plunged.

As the Congressional Budget Office noted in 2007, “Between 1991 and 2005, household earnings doubled (on average) in female-headed low-income households,” with the change “driven by a large increase in earnings during the late 1990s.” As household incomes swelled, poverty fell sharply — instead of rising as opponents predicted. For example, the rate and number of African American children in poverty reached record lows in 2001. By 2002, even the New York Times admitted “Welfare reform has been an obvious success.”

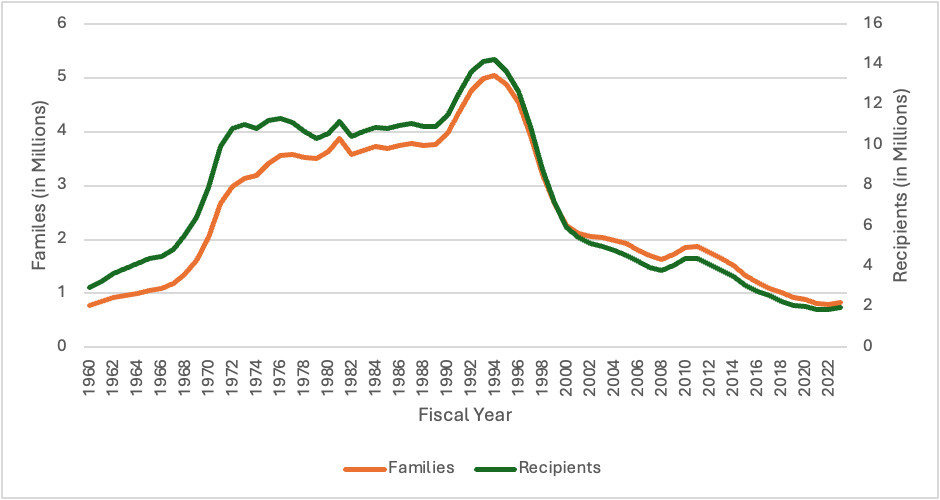

The caseload declines continued in most years since, with the recipient caseload falling to just under 2.1 million in 2024—an 85 percent total drop compared with 1995. Figure 1 displays the trajectory of the welfare caseload over that and prior periods on a family and also recipient basis:

Figure 1. AFDC/TANF Caseload in Families and Recipients, FY 1960-2023

Source: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Administration for Children and Families (ACF), Office of Family Assistance

Work requirements (which gradually phased in through 2002) and time limits have been widely regarded as the key contributing factors to those caseload declines. But many overlook the effect of the fixed TANF block grant, which immediately reversed the system’s misaligned financial incentives. Under AFDC, states with growing welfare caseloads were financially rewarded with more federal funding. Instead, the TANF block grant, set at about $16.5 billion starting in fiscal year 1997, offered states financial rewards for promoting more work and earnings instead of greater welfare dependence and poverty. Importantly, Congress also expanded the federal earned income tax credit (EITC) around this time, providing increased assistance to working families through that program rather than cash welfare.

Under the block grant, rapid TANF caseload declines meant average federal funds available to states per recipient of welfare checks rose sharply, more than doubling from $1,200 in 1995 to over $2,600 in 2000 before reaching $8,000 in 2024—more than triple the 1995 level in real terms. Federal funding available to states per family on welfare rose in similar fashion, from $3,500 in 1995 to over $7,200 in 2000 and nearly $20,000 in 2024—almost triple the 1995 level in real terms.

As one of us noted in October 2024 congressional testimony,

Under AFDC, the sharp welfare caseload declines witnessed since 1995 would have resulted in commensurate declines in federal funding. Instead, under the TANF program, federal block grant funding has been fixed at the record federal funding highs of the mid-1990s, unaffected by the large caseload declines since then. This reflects how the fixed TANF block grant has insulated states from what otherwise would have been sharply declining federal funding under the AFDC program, given such large caseload declines.

Had the federal government imposed work requirements and time limits without a block grant, funding would have declined as fewer families received the open-ended AFDC entitlement. Instead, sharp caseload declines combined with the fixed TANF block grant freed states to shift federal TANF funds to more productive uses like more child care and refundable state tax credits to promote work. In addition, the 1996 law allowed states that satisfied the TANF program’s increasingly strenuous work requirements to reduce state program spending to 75 percent of prior AFDC levels.

This reflects how the TANF block grant has been a remarkably good financial deal for states, even though the block grant has not been adjusted for inflation since it was set in 1996. Democrats regularly object to that fact, rightly arguing that the block grant has lost half of its real value over time.[1] Yet as the figures above display, TANF’s fixed block grant, time limits, work requirements, and associated policies resulted in caseloads falling even faster, leaving states with significantly greater funding per TANF recipient and family than ever before. When considering this fact along with the expansion of the EITC, states actually had more TANF funding to spend per recipient while the EITC continued to provide cash assistance to working families outside of TANF.

TANF Block Grant Savings

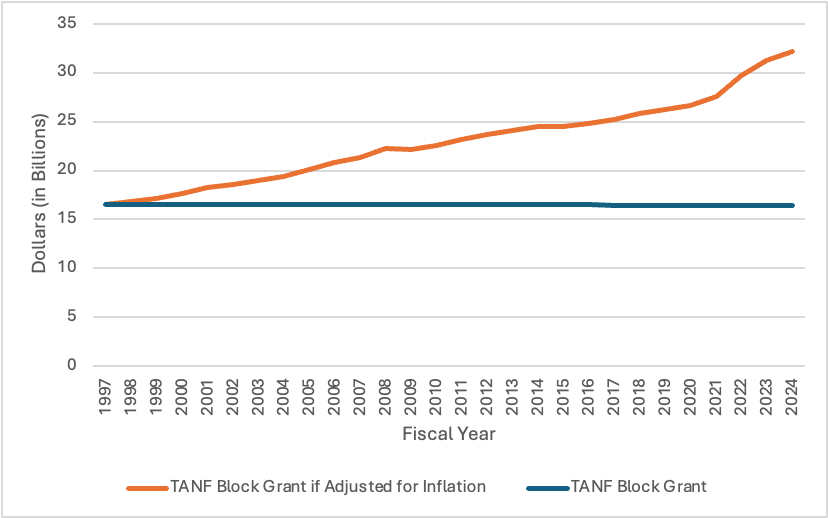

For federal taxpayers, TANF savings have been remarkable. The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office’s cost estimate for the 1996 welfare reform law projected savings of about $4.8 billion between 1997 and 2002 from ending several AFDC funding streams and replacing them with the fixed TANF block grant. It is impossible to know what AFDC spending would have been in the absence of welfare reform. However, simply the difference between the fixed TANF block grant and its inflation-adjusted value is an enormous figure. As displayed in figure 2, across fiscal years 1997 through 2024, that difference—in effect the savings from not including an inflation adjustment to the TANF block grant—totals $178.6 billion, or an average of $8.5 billion per year across the entire period.

Figure 2. Comparing the Fixed TANF Block Grant to Its Inflation-Adjusted Value, 1997-2024

Source: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Administration for Children and Families (ACF), Office of Family Assistance; and the U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS)

Even those large savings may be an understatement, as means-tested programs rarely grow at just the rate of inflation. For example, while the TANF block grant has remained fixed without even an inflation adjustment since fiscal year 1997, food stamp spending (under what is now called the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program or SNAP) more than doubled in real terms. Spending under that program increased from $41.9 billion in 1997 (in current dollars) to $100.3 billion in 2024 (which is down from a peak of $129.4 billion in 2022 in current dollars).

It is instructive to consider what would have happened if Congress had created a Food Stamp block grant in 1996 that tracked the terms of the TANF program. Those terms included setting annual federal payments to states at roughly the fiscal year 1995 level ($24.6 billion in nominal dollars, or $50.6 billion in current dollars) and holding that amount constant without adjustment for inflation since then. Compared with spending under current law, the total savings from 1997 through 2024 would have been $904.5 billion. Doing the same but adjusting the would-be food stamp block grant annually for inflation since 1997 would result in savings of $586.1 billion compared with current law.

Block Grants and Automatic Stabilizers

Some argue that the fixed TANF block grant undermines the program’s role as an automatic stabilizer. However, since its inception the TANF program has offered additional federal funding from a “Contingency Fund” when states experience demonstrated economic hardship. As the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities summarized in a 2024 report:

In addition to the basic block grant, some states can receive additional TANF federal funds from the TANF Contingency Fund. A state can access the TANF Contingency Fund if it meets a monthly economic hardship (or “needy state”) trigger and spends more MOE funds than are otherwise required. (See below for more on MOE.) Congress created this $2 billion fund when it created TANF to provide additional help to states in hard economic times. States made little use of it until the Great Recession, but they began to draw on it in 2008, and nearly half of the states have done so since then. Since the original $2 billion provided was depleted early in fiscal year 2010, Congress has added limited funds ($608 million) for each year; qualifying states have received less than half of the amount for which they qualified each year since 2010.

In addition to the TANF Contingency Fund that is payable under permanent law, as is described in greater detail below, states also have accrued significant and recently growing unspent federal TANF balances, which could be drawn down when needs grow.

Congress also regularly provides temporary boosts in federal funding during recessions. For example, during the Great Recession, President Obama signed into law a $5 billion “Emergency Contingency Fund for State TANF Programs,” payable to states that experienced growing TANF caseloads or other measures of need. During the pandemic, the American Rescue Plan Act authorized a Pandemic Emergency Assistance Fund providing $1 billion for TANF agencies to assist needy families. Far more consequentially, multiple federal benefits were created or expanded in ways that provided significant assistance to low-income families with children. These benefits included large federal stimulus checks, expanded child tax credit payments, expanded SNAP benefits, expanded Medicaid coverage, and unprecedented unemployment benefits payable even to those not previously employed.

If block grants were applied to other programs like SNAP or Medicaid, similar contingency funds could be created or temporary expansions could be legislated during recessions.

[1] Despite their objections to the lack of an inflation adjustment, Democratic members of Congress regularly vote for legislation providing short-term TANF extensions that maintain current funding levels. The recent Continuing Resolution is a significant exception to that rule. Even during periods when Democrats controlled both houses of Congress and the White House, the TANF block grant has remained fixed at the 1996 level.