The rise of artificial intelligence (AI) has ignited fears about its potential to disrupt the labor market. There has been no shortage of predictions of huge impacts AI will have on the future of work—especially for workers with higher levels of education—fueling both anxiety and the risk of overzealous regulation. A recent report from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) may help calm some of these fears.

OECD finds that many high-skilled workers with greater AI exposure have experienced employment gains over the past decade, suggesting that AI is not eliminating human jobs as much as it is creating new tasks and opportunities. This so-called “reinstatement effect” of AI is consistent with a recent NBER study of employment in 16 European countries between 2011 and 2019 that found AI was associated with increased white-collar employment and few impacts on employment levels or wages for lower skilled jobs.

Beyond the job numbers, the OECD report also highlights several less discussed AI impacts, on job satisfaction, job performance, health, and wages. Sixty-three percent of workers using AI say that the technology has changed their job for the better, leading to greater enjoyment of their work. Across a number of indicators, workers in the finance and manufacturing sectors noted significant improvements in performance, enjoyment, and physical and mental well-being as a result of using AI on the job. In both sectors, nearly half of those surveyed said AI has improved fairness in management and can help disabled workers.

A 2022 Github survey reported similar findings. Users of Github’s AI code-writing assistant Copilot said that the tool helped them stay in the flow and maintain concentration during repetitive tasks. A strong majority of Copilot users said AI made them feel more fulfilled with their job, less frustrated when coding, and better able to concentrate on higher-value and more satisfying work.

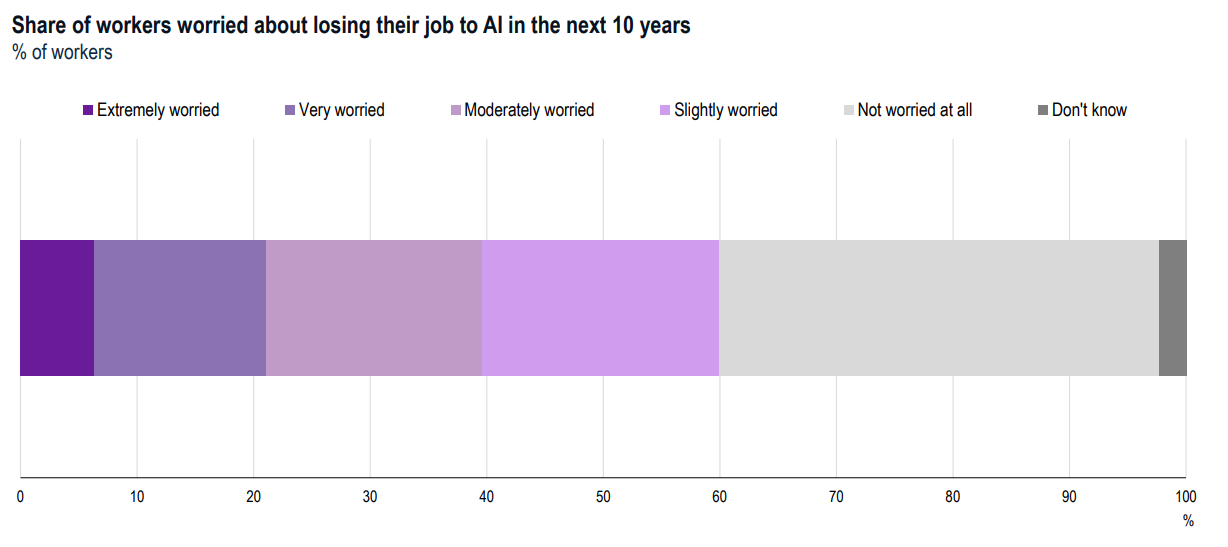

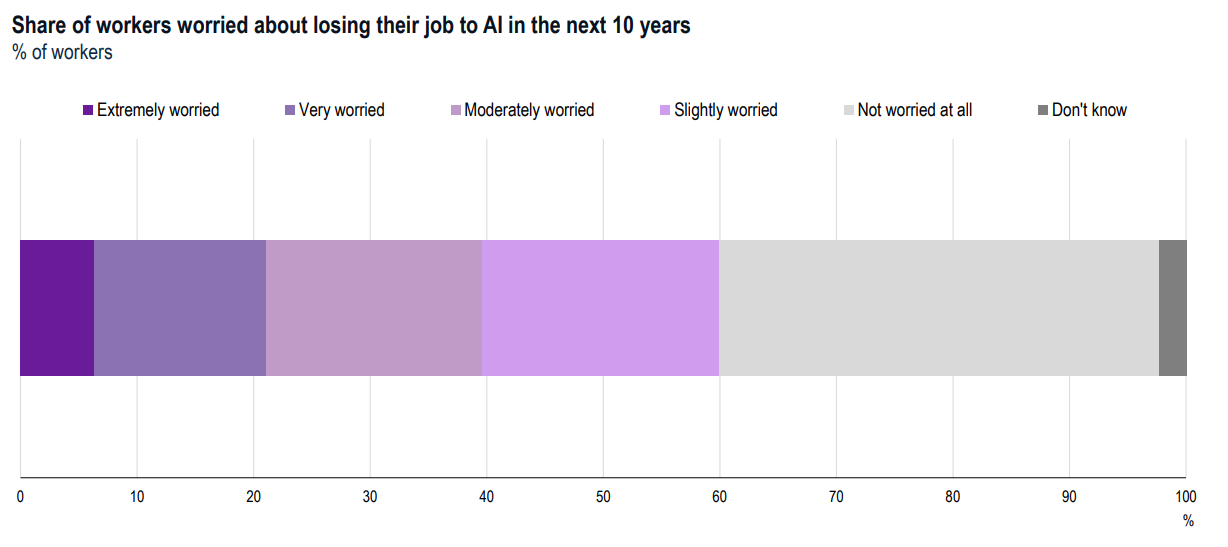

The trade-off appears to be rooted mostly in the unknowns of AI. The OECD found many workers were anxious that AI will give employers high-powered tools that can erode their privacy. Nearly 40 percent are at least moderately worried about losing their job to AI within the next 10 years.

AI is not a panacea, and nor will it be an instant fix for long-term challenges like sluggish productivity growth. It does appear, however, to hold promise in a few key areas. In addition to improving job satisfaction for all, AI may–somewhat counterintuitively–disproportionately benefit lower-skilled workers. In April, a Stanford study of customer service workers at call centers found the use of AI boosted productivity and quickly brought low-skilled workers up to levels of performance typically seen among their highest skilled counterparts. And a March working paper by MIT researchers documented how use of ChatGPT increases job satisfaction and productivity in writing tasks, especially among less skilled workers.

Perhaps, then, AI will turn out to be a tide that lifts all workers rather than a job-destroying technological tsunami. Higher-skilled workers may benefit from the new roles AI is likely to create while those with less education and experience can use AI to supplement in areas of weakness, increase their autonomy at work, and position themselves for career advancement. And, by helping us execute repetitive, draining tasks, it can free all workers up to do more creative and fulfilling work. What this adds up to is a future in which AI creates both winners and losers in terms of job creation and displacement. The most important factor in determining where one lands in this equation is preparing now for the opportunities, and challenges, this important new technology presents.