One of the most controversial policies included in H. R. 7024, the “Tax Relief for American Families and Workers Act” that passed the House on January 31, is a provision that would expand the “lookback” to determine eligibility for the child tax credit (CTC). Under current law, adults claiming the CTC for a tax year must have had earnings in that year. But under H.R. 7024, adults could claim the CTC provided they worked in either of the past two tax years, severing the program’s annual work requirement for claiming this important benefit.

The “lookback” policy reflects a halfway point between current law and Democrats’ desire to turn the CTC into an unconditional government payment—reviving the temporary policy they enacted on a partisan basis in 2021. That 2021 policy resulted in CTC payments flowing for the first time to nonworking parents, eliminating both the work requirement and work incentive for claiming the credit and effectively reviving work-free welfare checks. That goes against the very nature of a tax credit such as the CTC, which is, by definition, intended to offset income and payroll taxes for tax filers with children, which in turn requires employment in the household.

Meanwhile, many other government programs are actually intended to support non-working households with children. In light of such other programs, suggestions that the lookback policy is needed to protect individuals against declining or ceasing earnings is highly suspect. For example, some describe the lookback policy as “a form of wage insurance,” recalling a program some liberal lawmakers proposed—and failed to enact—before the Great Recession. Authors affiliated with the liberal Center on Budget and Policy Priorities suggest the lookback policy will allow families to avoid a drop in the CTC if their earnings decline because an adult “lost a job, faced health or caregiving needs, or welcomed a new child.” They term the overall CTC proposal “modest in size and impact.”

These contentions are wrong in two important ways.

First, the expanded lookback is unlikely to be “modest in size and impact.” Much attention has been paid (including by us) to the work disincentives it creates. In a review we authored with AEI colleagues in January 2024, we found that the lookback provision alone would result in a net 150,000 fewer parents working each year. But while critics have tended to dismiss that effect, few have noted that, under current law, a far larger number of parents already work in one year and not the next. According to our analysis using data from the Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey, we found that more than 1.6 million tax units already followed this pattern in the years before the pandemic. That’s hardly a small number, and in fact is roughly double the number of families currently collecting assistance under the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) cash welfare program. The expanded lookback policy will provide new CTC benefits to households only marginally attached to the labor force. And supporters of this change will undoubtedly use it to push for even greater CTC expansions during tax negotiations next year.

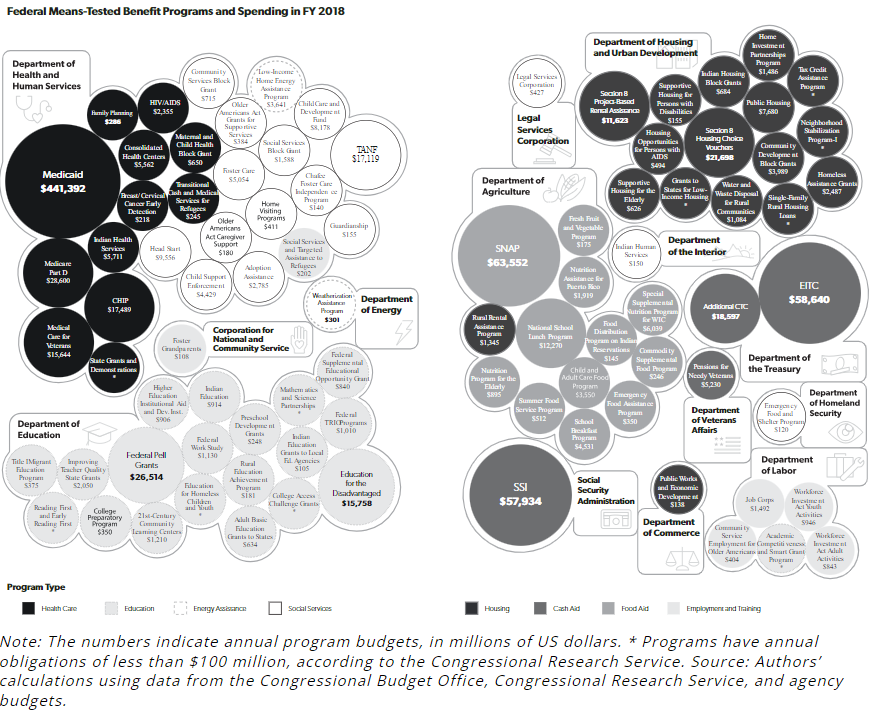

Some might believe that the existence of families with no or very low earnings for an entire year is the reason we need the CTC lookback policy. This contention is also misguided, bringing us to a second, and even more important, point. Advocates for an expanded CTC often leave the impression that families need it as protection against declining wages, and that in its absence they will have no assistance. For example, during Committee consideration in the House, Rep. Gwen Moore (D-WI) characterized the effect of an amendment providing the CTC to non-workers this way: “Even if your parent is poor, baby, we are not going to let you starve.” But that view completely ignores dozens of nutrition and other current safety net programs depicted below that assist low-income parents, along with major social insurance programs and even privately-funded benefits that specifically target non-workers.

Consider just some of the major social insurance, employer-funded, and safety net programs that already assist families facing temporary unemployment or who are otherwise marginally attached to the labor force:

Examples of Non Means-Tested Benefits

- State unemployment insurance (UI) benefits are always available to workers laid off by a covered employer, including unemployed parents. (UI does not cover the self-employed and independent contractors, although Congress created a temporary, and widely-defrauded, program providing separate benefits to those groups during the pandemic.) UI provides benefit checks that currently average over $440 per week nationwide and can last for up to six months. Benefits replace a significant share of prior earnings, based on progressive formulas that advantage lower-income individuals. Prior earnings needed to qualify are very low. For example, in California workers can earn as little as $1,125 in one year to qualify for UI checks in the next. However, applicants must have some prior employment history and have to be laid off through no fault of their own to qualify (i.e., those who quit their job or are terminated for cause are not covered).

- Federal unemployment benefits paid during recessions offer additional weeks of checks to the long-term unemployed (that is, generally beyond six months, continuing state UI check amounts). During the last two recessions, maximum durations stretched to over 18 months and federal funds also expanded weekly benefits, including by a record $600 per week at the start of the pandemic.

- Private and state-funded short-term disability benefits can replace lost wages for those whose illness or injury causes temporary unemployment and who are not eligible for UI because they are unable to work. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 42 percent of workers have access to short-term disability assistance from their employers and 26 percent from a state or local government.

- Worker’s compensation is less common because it covers only employees who are injured on the job. Nonetheless, state governments require employers that meet certain criteria to provide compensation to replace lost wages for injured employees.

- Federal long-term disability benefits are payable to disabled individuals with significant work records under the Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) program. SSDI benefits average almost $1,400 per month per recipient, and also cover spouses and children.

- Paid leave is provided by either private employers or state and local governments to replace wages when employees need time away from work. According to a Bureau of Labor Statistics survey from 2018, 66 percent of all workers had access to paid leave benefits. Of those, 94 percent could use it for time away due to their own illness, 78 percent for the illness of another family member, 76 percent for the birth or adoption of a new child, and 64 percent for childcare.

Examples of Means-Tested Safety Net Benefits

- Federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits (formerly called food stamps) target low-income households and have a much higher coverage rate than UI. Currently, over 20 million households receive SNAP (including 7.8 million households with children and covering 42 million individuals in all). Benefits for a nonworking family of four with no other income totals $973 per month or $11,676 per year. SNAP has no work requirements for adults in households with children.

- Cash welfare checks are a significant share of the wide-ranging assistance that the TANF program provides to some 800,000 families with children, including almost two million individuals. Unlike the earned income tax credit (EITC), which requires recipients to have earnings to qualify, TANF assists low-income parents and children facing temporary unemployment. TANF requires participation in work activities of able-bodied parents without employment and states cannot provide families federal dollars for longer than five years, but states can extend the time limit and often provide benefits only to children in the household. Benefit types and levels vary by state, but a single mother with two children can collect $736 per month in New York City and $653 per month in Wisconsin, without counting child support, SNAP, Medicaid and more for which she might be also eligible.

- Federal long-term disability benefits are also payable under the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program to low-income disabled individuals with more limited work histories than those who qualify for SSDI. SSI benefits average over $700 per month for working-age adults, and are also payable to disabled children.

- Medicaid provides health coverage to millions of low-income children and parents. The Children’s Health Insurance Program provides health insurance to uninsured children whose family incomes are too high to qualify for Medicaid.

Beyond these programs, personal savings and family support can also help families address short-term spells of unemployment or earnings loss. For those families whose low incomes make savings and family support challenging, the dozens of other programs depicted above provide additional food, housing, health care, transportation, energy, and other benefits and services.

Ignoring this expansive system of safety net and other benefits for people facing temporary unemployment or marginal attachment to the labor force offers a distorted view of the substantial and growing support taxpayers already provide to assist families with declining, sporadic, and even no income from work.