It would be a king-sized understatement to say that diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives have had better weeks, months, years, and decades than they are currently experiencing. From the Supreme Court’s ruling that banned affirmative action in admissions, to the Trump administration’s full-scale bureaucratic offensive to expunge DEI from federal policy and programs, to corporate America’s widespread retreat from years of promoting DEI, rarely has a social movement experienced such a decisive setback.

The hopeful view of these developments is that they are a reassertion of core American values, like merit, individual rights, and freedom of speech. It’s certainly true that DEI and race-focused affirmative action have always lived in an uneasy tension with American ideals. Our founding documents—not to mention our entire national ethos—are rooted in moral and political equality among people. In application, those principles haven’t always been honored (ask blacks, women, native Americans, and sexual minorities for the details), but even the sad chapters of discrimination and remediation are a testament to the enduring strength of the values themselves.

Still, the full elimination of DEI-type policies and programs, which seek to address historical patterns of disadvantage, also risks contradicting American values. Americans despise unfair advantage and love the underdog. We recognize that many start life with overwhelming head starts while others, through no fault of their own, are born into circumstances that make achieving the American dream of social and economic progress an uphill fight. Insisting on equality is one thing; achieving a society where advancement is genuinely open to all is another. How can we promote opportunity for those at the periphery of American society without falling into the cultural, political, and constitutional trap created when we use race as the singular proxy for disadvantage?

In a 2023 National Affairs essay, I laid out the case for an alternative to race-oriented DEI and affirmative action. My argument is that what really holds disadvantaged communities back today are invisible yet very real limitations that arise because of socioeconomic status rather than race—even if race has often played a part in causing the disadvantage. Controlling for race and focusing on socioeconomic status helps bring this reality into focus. For instance, in one AEI study of housing value disparities, when the data was controlled for numbers of single-borrower mortgages and credit scores—proxies for single parent homes and economic status—home values in low-income white neighborhoods were virtually the same as in low-income black communities. This means that property value differences are overwhelmingly the product of socioeconomic status rather than racial discrimination. Analogous effects can be seen in marriage rates, nonmarital births, educational failure, substance abuse, and criminal justice involvement. All these negative outcomes manifest across racial groups and differences between groups tend to narrow when controlled for socioeconomic status. As much as we subconsciously associate poverty and race, we are often blind to the fact that disadvantaged communities are living similar realities irrespective of racial composition.

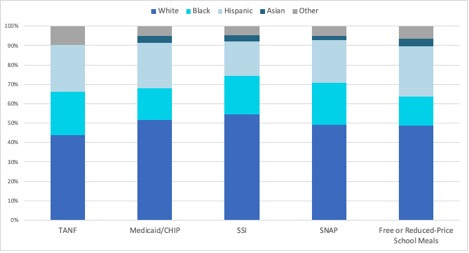

This shared reality is reflected in welfare spending. In absolute numbers, whites make up the largest share of recipients in most of our federally funded welfare programs (Figure 1). As Congress and the administration considers deep cuts to safety net programs like Medicaid and SNAP, paying attention to welfare dependency among whites seems like a good idea.

Figure 1. Percentage of Public Assistance Recipients, by Race

Distribution across key federal programs (2022)

Source: US Census Bureau, 2022

It’s important to remember that when he was preparing to announce his War on Poverty, Lyndon Johnson didn’t travel to an urban center; he went to Appalachia, which was then—and remains today—one of the most socioeconomically disadvantaged regions of the country. Using race as the singular proxy for disadvantage stirs resentment and leaves some of the most disadvantaged communities in the country—particularly rural places—out of our consciousness when it comes to long-term, systemic disadvantage and intergenerational poverty. Racial minorities suffer from stereotyping while low-income white populations are neglected. Everybody loses.

Lyndon Johnson in Martin County, Kentucky, April 1964.

In recent testimony to the US Senate Committee on Aging, I reflected on the challenges we face in failing to address systemic disadvantage and how that failure is at odds with the nation’s moral legacy and its current economic interests. America, like the rest of the world, is aging. In 1960, the average American was 29.5 years old. Today that figure is closer to 40. The US population pyramid is increasingly top-heavy, with larger numbers of retirement-age people and fewer children and young adults. As has been widely discussed, demographic aging is making many of our major entitlement programs, like Social Security and Medicare, unaffordable as the ratio of active workers to retirees continues to narrow.

Less commented upon is how our older, greyer population also has consequences for employment and economic growth. Between 2000 and 2005, the US working-age population grew by 12 million workers, while during the 2017 to 2022 period, it only grew by 1.7 million. Crashing labor supply growth is already constraining activity in construction, agriculture, and hospitality, contributing to worker shortages and rising prices. Further, demographic stagnation often contributes to lower economic growth over time.

Unless we wish to accept lower growth and declining standards of living, we need solutions to the demographic/economic growth crunch that is already upon us. Our options for doing so are limited. Labor supply can be stretched via automation and efficiency measures (like artificial intelligence) and supplemented by fixing the nation’s broken immigration system, though neither seems likely to provide short- and medium-term relief for worker shortages. As a matter of national interest, we simply must get more out of our human capital base, and that means bringing more lower-propensity workers (e.g., those dependent on welfare, men who have dropped out of the workforce, older workers, the disabled, and other disadvantaged groups) into the job market. Inclusion policies for education, training, and employment focused on socioeconomic disadvantage are more than just a “nice” thing; they are essential.

The extreme lengths to which its advocates took DEI contradicted deeply held national values of equality; that’s what made it unsustainable. America will be better served—economically and in terms of social harmony—by a race-neutral policy approach that seeks to level the playing field for all those who face barriers that inhibit their ability to contribute to our society and economy. This is our new frontier, fulfilling the promise of a society in which all people are treated equally and as deserving of an equal chance at life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.