Lessons of the post-COVID economy.

When voters tell you what they are concerned about, believe them. Exit polls from the presidential election the show that the economy ranked first among voters’ concerns at 32 percent, almost three times more than the next closest issue, immigration. A plurality of voters—45 percent—said that their financial situation was worse than four years ago. As many commentators have noted, this concern about the economy seems starkly at odds with actual economic conditions: very low unemployment and inflation that has fallen almost to the Federal Reserve’s 2 percent target. Not too shabby for an economy that has led the world in the post-COVID recovery.

A recently revised 2023 study by MIT’s David Autor and his collaborators, Arindrajit Dube and Annie McGrew, adds to the mystery of the disconnect: Over the past four years, wage inequality has shrunk dramatically.

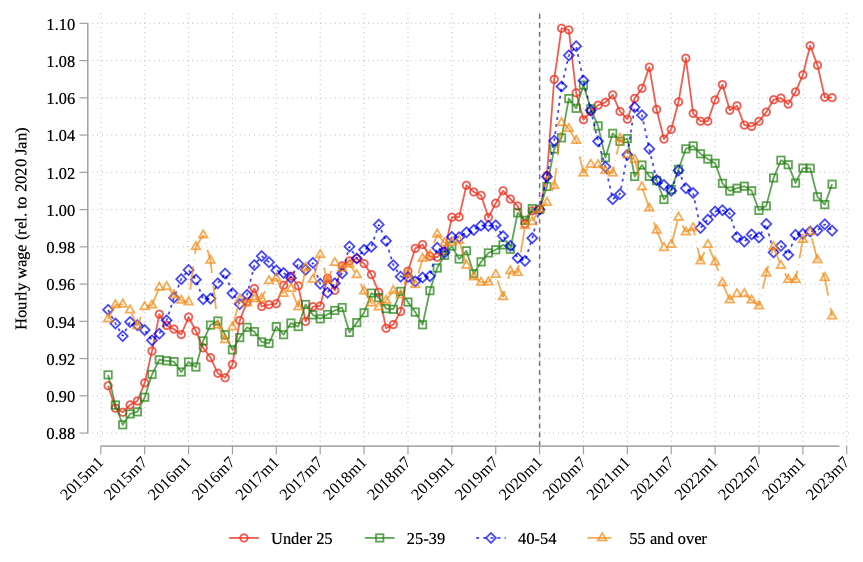

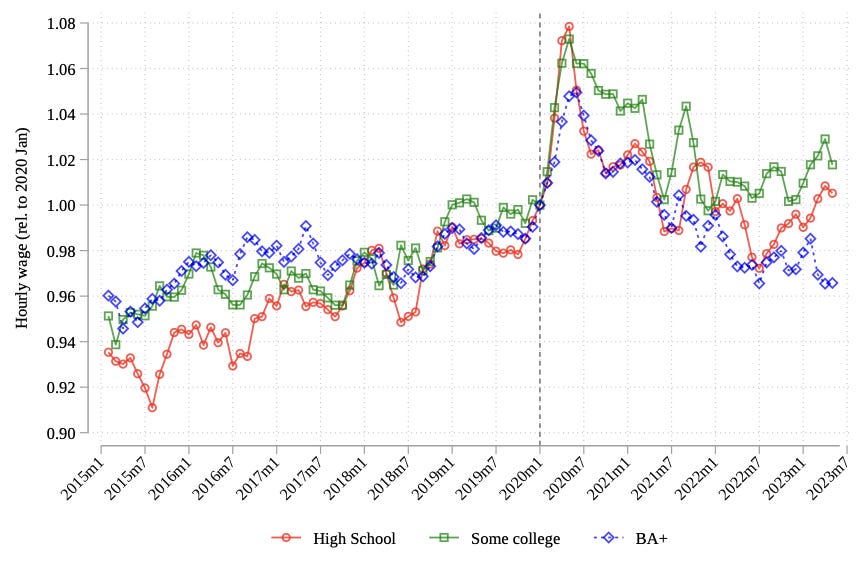

Since the 1980s, wage inequality has been mostly a one-way street, with the benefits of wage growth going to those with more education and skills while those with less have seen lower wage growth. This makes it surprising, to say the least, that Autor et al. find that since 2020, real wage increases among workers without college degrees have reversed nearly one-third of the cumulative rise in wage inequality from1980 to 2019. They call this phenomenon the “unexpected compression” of wages, which harkens back to its only real analogue, the “great compression” that occurred during and after World War II. The overall trend has been that the wages of younger, less educated workers have risen quickly while wages at the top remained relatively flat, especially for workers with bachelor’s degrees.

Trends in Real Hourly Wages by Age and Education 2015–2023, Relative to January 2020

Both graphs from Autor, et al., “The Unexpected Compression,” NBER, May 2024.

The theory of what caused the compression goes like this: Following the peak of the pandemic, lower-wage workers experienced the most favorable labor market conditions in living memory. Plentiful job opportunities led to a sharp increase in worker risk tolerance for job changes. More frequent job changes helped less educated, lower-skilled workers climb the wage scale.

The authors argue that this wage growth is not merely a result of businesses “bidding up” wages; rather, it reflects a fundamental shift in the nature of job-switching as workers moved from lower-productivity firms to higher ones. This reallocation of workers to more productive firms and tasks, along with technological innovations and a surge in the creation of new businesses, may be part of the recent acceleration in U.S. labor productivity.

From a workforce-development standpoint, the role of businesses in driving the reallocation of workers from less to more productive work is critical. With a few exceptions, our public workforce-development programs show scant evidence of improving employment opportunities and wages for lower-skilled workers. If the MIT study is correct, a highly competitive labor market, driving both wage growth and the reallocation of workers to more productive tasks, may be one of the most important factors in improving wages and reducing inequality.

Of course, this isn’t an either/or proposition. Workforce-development policy that enhances worker flexibility—through, for example, worker-directed retraining, reskilling, and relocation resources—is important to helping individuals and the broader labor market succeed. So are the tax incentives for employer investments in skills development. Every bit helps.

At the same time, the nation’s underlying economic policies, and the extent to which they help maintain strong growth, do the most to help workers advance to higher paying positions. If we can get all the arrows—economic growth, investment in skills, and employer training incentives—pointed in the same direction, American workers could find themselves on the cusp of a new age of opportunity, economic flourishing, and greater equality.