Marriage rates in America are falling fast: Many men and women are marrying later, and more and more people are never marrying at all. Marriage is in retreat for a host of reasons, but one overlooked cause is the rising difficulty many young people have finding a partner who meets all of their requirements—emotional, physical, financial, and political. That last requirement has only become more important over time, with fewer Americans willing to date or marry across the aisle.

Dating apps and websites report a growing share of users setting political criteria for matches. The Survey Center on American Life, a project of the American Enterprise Institute, recently found that about two-thirds of liberal and conservative singles would be more likely to “swipe left” and reject a potential match who did not share their politics.

This bodes ill for the future of marriage—given that growing numbers of young men and women find themselves on different sides of America’s deepening political divide. (We base our following analysis on the fact that most young adults who marry will do so with a different-sex partner—according to Census Bureau data, heterosexual marriages accounted for about 98 percent of weddings of people under 35 in 2021.)

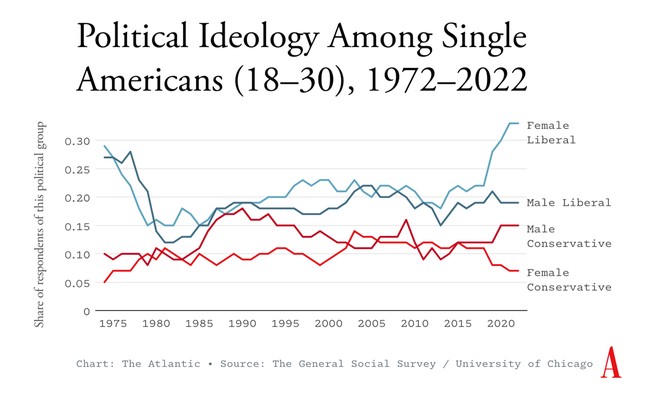

The nonpartisan General Social Survey, run out of NORC at the University of Chicago, has been collecting data on young people’s political attitudes since the early 1970s. We’ve found that focusing on singles ages 18 to 30 and pooling data across five-year intervals is a useful way to ensure a large enough sample to track accurately how attitudes in early adulthood have shifted over time. The figure below shows the share of young singles (18–30) in the survey who identified as distinctly liberal or conservative (excluding respondents in the middle who answered as “slightly liberal,” “slightly conservative,” or “moderate, middle of the road”).

The most striking aspect of these trends is that the past decade has seen the sexes polarizing along ideological and political lines, a pattern that coincides with the rise of social media and the post-Trump political landscape. Young single men have been moving to the right, even as their female peers have been moving even further left. About 10 percent of such men were conservative in the early 1980s, but that share has now risen to about 15 percent (while the proportion of single liberal young men has held steady at about 18 percent in recent years).

As for single young women, the share identifying as liberal surged from about 15 percent in the early 1980s to 32 percent in the 2020s. (Correspondingly, the share of conservative single women declined from 10 percent to about 7 percent over the same period.) Most of this change has happened since 2010. In short, the past decade has seen single young men shift slightly to the right and single young women move markedly left, which means that the ideological divide between the sexes is growing.

This poses a major challenge for people looking to marry, given that many of today’s young adults show a growing preference for partnering with someone who shares their politics. Granted, partisanship as a determinant of the choices people make in love and marriage is not a wholly new phenomenon: Americans have been sorting partners by politics for decades. This is a wise strategy for most people—assuming that, for many, an ultimate goal of dating is to find a spouse—because research suggests that marriages across political or religious lines (when those things matter significantly to each partner) can be less happy, more conflicted, and more likely to end in divorce than marriages where spouses agree on religion and politics.

However, plenty of evidence suggests that marriages between like-minded spouses are stronger; scholars call such relationships, in which the two partners share important characteristics, “homogamous.” Homogamy matters for marriage when it predicts how a person thinks about their life goals, their ways of resolving conflicts, and their values regarding work, family, faith, and fun. Clearly, for many people, religion is very bound up with such attitudes, but the benefits of homogamy certainly don’t end there. For example, it turns out that even highly narcissistic people are happiest when married to other narcissists, according to a 2020 study.

A lot of people might swipe left for narcissists, too, so where does politics fit in? Recent research suggests that politically homogamous couples really do enjoy greater relationship satisfaction and lower divorce rates. Wendy Wang, the director of research at the Institute for Family Studies, where we are both fellows, has found that fewer than half (47 percent) of politically mixed married couples report they are “completely satisfied with their family life,” compared with “61 percent of couples in which both spouses are Republicans and 55 percent where both are Democrats.” Besides being more likely to share a range of values, couples on the same political team are likely to find it easier to build friendships in common, especially given the polarized character of today’s society.

The values and attitudes encapsulated in religious and political ideologies also act as a reliable proxy for long-term life goals—especially regarding gender, work, and family—that have a big bearing on whether marriages succeed or fail. For men and women who have similar political views, forming a bond with a mate is simplified. But for those with very different political views, matching is a tougher challenge. Because fewer heterosexual men and women will be able to find a partner who shares their politics, more people may never marry at all.

Liberal women and conservative men who want to marry face a particular challenge: Not enough single partners of the correct political persuasion are available today. In broad terms, there are only 0.6 single liberal young men for each single liberal young woman; likewise, only 0.5 single conservative young women exist for every conservative young man. Statistically, in other words, about half of these ideologically minded young singles face the prospect of failing to find a partner who shares their politics.

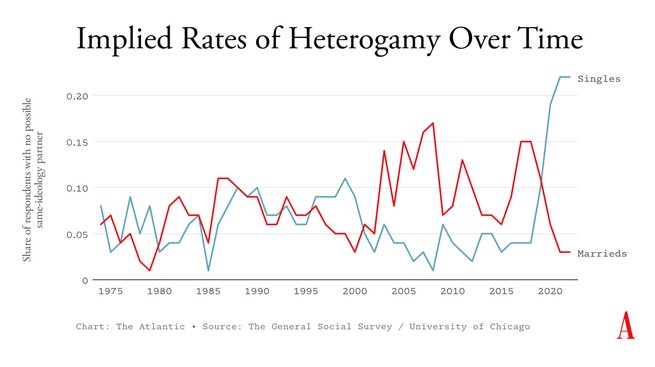

The possibility that growing political heterogamy between young single men and women is a barrier to happy, lasting marriages becomes clearer when we compare these ideological gaps among single and married people. The chart below shows how unbalanced the ideology gaps by sex are among single people and married people under age 30, based on our analysis of the General Social Survey. Among several assumptions we needed to make for this analysis was that each person would marry within their same age group (to arrive at the “implied rate”); we then estimated the shares of young singles and marrieds who mathematically must be partnered with someone with different politics, given the ideological composition of the married and single groups.

Since the 2010s, the rate of ideological heterogamy that is required to match all singles has risen sharply, from about 6 percent in the 1970s to 22 percent today. In other words, about one in five young single adults today will have to put a ring on someone outside their ideological tribe if they wish to marry—a consequence of the fact that far more single conservative men than conservative single women now exist, as well as far more single liberal women than single liberal men.

By contrast, despite an anomalous spike in the mid-2000s, the implied heterogamy among married people is about the same today as it was in the 1970s; indeed, “marrying across the aisle” appears to be falling in popularity even though young people are becoming more politically polarized by gender. The fact that no increase in heterogamy has occurred among the marrieds tells us that even as the possibility of finding a mate who shares one’s politics shrinks, Americans are not budging on their preference for same-politics partners.

The sobering future for marriage and family life in America is that greater political polarization spells trouble for already anemic rates of dating, mating, and marrying. And not only in America—we are seeing this dynamic play out in other countries. Recent research in Singapore has found that divergent attitudes between men and women about politics, family, and gender roles are a crucial factor in low marriage rates. Similar effects can be seen in South Korea, where rates of marriage and fertility have hit world-historical lows.

The divide between the sexes in America is not as deep as it is in parts of East Asia, but the U.S. is in danger of heading in that direction. And if the sexes are making war over political issues, they’re less likely to make love.