Data analysis is hard. Admittedly, the consequences of getting it wrong are less severe than a botched surgery. But you still want to be very careful. It’s all too easy for a misinterpretation of the facts to harm important policy debates.

For an example, look no further than the debate over the past couple of days as to how many Americans wish they could be employed in manufacturing. The debate began on Sunday with a data-heavy op-ed in the Financial Times by Tej Parikh lamenting American nostalgia for manufacturing. Citing the Cato Institute’s 2024 Trade and Globalization National Survey, Parikh claimed that “only one in four [Americans] believe they would be better off in a factory over their current employment.”

The accompanying chart was then tweeted out by pollster Frank Luntz midday. Luntz included a more detailed breakdown from the survey, which asked respondents whether they agreed that, “I would be better off if I worked in a factory instead of my current field of work.” Luntz described the results as 25 percent saying they agreed, 73 percent disagreeing, and 2 percent who “currently work in a factory.” Luntz found the result to be more ambiguous than Parikh did, noting that it might suggest that over ten times as many Americans are interested in factory jobs than actually work them.

By Monday morning, American Compass’s Oren Cass had expounded on the Luntz tweet in a Substack column, saying that “if fully 25% of poll respondents say they’d prefer a factory job to their current job, that suggests massive potential unmet by the current labor market.”

However, there’s a problem here. Luntz linked to the Cato survey results but failed to catch that the question about factory work was asked of only a subset of respondents. Specifically, it excluded retirees as well as those currently employed in manufacturing. The 2 percent that Luntz said “currently work in a factory” (actually “in manufacturing”) slipped through this screen for some reason (perhaps because their factory job is a second job). It’s not the case that just 2 percent of workers are in manufacturing, as we’ll see.

Emily Ekins, Cato’s Vice President and Director of Polling, was kind enough to share with me the microdata collected for the survey. That microdata allows analysts to get behind the summary results to which Luntz linked.

The Cato data (collected by YouGov) indicates that if one excludes retirees but includes everyone currently employed in manufacturing, then 24 percent of Americans agreed they “would be better off if [they] worked in a factory instead of my current field of work.” That compares with 69 percent who disagreed. Meanwhile, 6 to 7 percent were currently employed in manufacturing. We can sum the shares who think they’d be better off in a factory job and who actually work in manufacturing and take it as an indicator of potential interest in manufacturing jobs. That sum is 4.8 times actual manufacturing employment. The same figure using the (incorrect) estimates in Luntz’s tweet would be 13.5 times actual manufacturing employment ((25+2)/2).

It’s worth noting that most people who thought they’d be better off in a factory job only “somewhat” agreed rather than “strongly” agreeing. The number strongly agreeing they’d be better off was the same as the number actually working in manufacturing, so what we might call strong potential interest in manufacturing jobs is about twice actual manufacturing employment.

All these figures include people who are not employed. Among people who were unemployed, for instance, 29 percent agreed they’d be better off working in a factory. But presumably many of them would agree they’d be better off working—period. It’s hardly a special endorsement of factory jobs.

There’s a similar ambiguity for people who are neither working nor looking for work. Among homemakers, for instance, 27 percent said they’d be better off working in a factory. One in five permanently disabled people said they’d be better off working in a factory. Among students, the figure was 22 percent. Would they prefer non-factory jobs to factory jobs? We don’t know. It’s not even clear what it means, for instance, that some permanently disabled people not looking for work think they’d be better off “if [they] worked in a factory instead of my current field of work.”

If the question is how many workers have manufacturing jobs or think they’d be better off with a factory job, we can drop everyone except the currently employed. In that case 9 percent of workers are employed in manufacturing, while 24 percent think they’d be better off in a factory job. That puts potential interest in manufacturing jobs at 3.7 times actual manufacturing employment, but strong potential interest at just 1.7 times the current level.

In some ways, the cleanest subgroup to consider is full-time workers. For them, preferring a factory job is a clear indication that they value manufacturing work per se, as opposed to preferring a job to no job or full-time work to part-time work. Among full-time workers, 22 percent agreed they’d be better off in a factory job, while 10 percent currently worked in manufacturing. Potential interest in manufacturing jobs is 3.2 times actual employment in manufacturing. Strong potential interest is 1.6 times manufacturing employment.

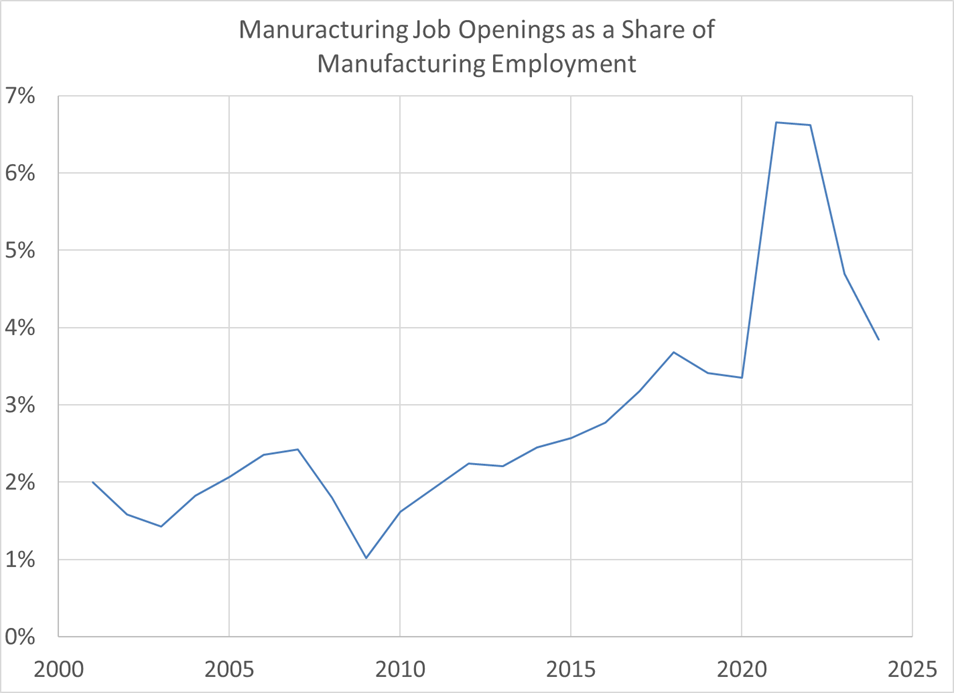

These estimates would be more meaningful if not for the fact that “potential interest” in manufacturing jobs is similarly high for homemakers, students, and disabled people not looking for work. They would also be more compelling as evidence for latent demand for manufacturing jobs if job openings in the sector were becoming scarcer relative to manufacturing employment, instead of more prevalent.

Moreover, we should not assume that “potential interest” in a job relative to actual employment would be smaller if instead of asking about factory work, the survey had asked if respondents would be better off in, say, a retail or service-sector job. That “potential interest” might be high relative to the number actually employed in the retail or service sectors. There will always be some workers in jobs that are a relatively poor fit.

There will also always be armchair populists like Oren Cass claiming to “understand America” in a way that hopeless “neoliberals” will never get. Their claims would be more credible if they showed greater care in their data analysis and said less in the absence of data.

Cass rebukes the 20 percent of Americans who, according to the Cato survey, disagree that “America would be better off if more Americans worked in manufacturing than they do today.” But the survey also shows that actual manufacturing workers, by a statistically significant margin of 29 percent versus 19 percent, are more likely than other Americans to reject the Cass view that more manufacturing employment would be better. If that’s any indication, bringing manufacturing jobs back to America would make workers less excited about them, not more. (And don’t tell them what would happen to the prices they pay for goods or how it would impact their ability to afford services!)