Republicans and Democrats alike agree about the importance of workforce training. They’re right: Despite a recent labor-market cooling, there are still 7.7 million unfilled jobs in the United States.

Unfortunately, America’s workforce-education system is a patchwork of dubious efficacy. Workforce programs are underfunded, tangled in red tape, and often fail to achieve their goals. Fixing this is hard: There’s too little rigorous research on what works to get jobseekers off the sidelines and into the economy’s most in-demand occupations.

But one state has made more progress than most. In 2016, Virginia created FastForward, a network of courses at the state’s community colleges that aims to provide quick job training for a low cost. While the model has long showed promise, a new analysis by the Annenberg Institute at Brown University confirms that FastForward led to substantial increases in wages for its participants.

The FastForward Model

The Virginia legislature created FastForward in 2016. Operated out of the state’s 23 community colleges, FastForward trains workers to earn industry-recognized credentials that enable them to join high-demand occupations. In particular, FastForward aims to prepare workers for “middle-tier” occupations that require some education beyond high school but not a four-year degree.

FastForward courses range from six to 12 weeks in length. The programs do not operate on a traditional semester basis; you can sign up for a course beginning next week if you choose. Many programs hold classes on weekends to accommodate working learners. At the time of this writing, students could select one of 892 different courses, which commence at various points over the coming months.

Participants do not earn college credit for completing a FastForward course, but they do have the opportunity to take an exam to earn an industry-recognized credential in their chosen field. For instance, students who complete a commercial driver’s license (CDL) course are eligible to take the CDL exam at their local Department of Motor Vehicles. Students who pass may then start careers as professional truck drivers.

The commercial driver’s license is the most popular FastForward course, but the state offers programs in a diverse range of industries. Other popular courses include training to enter the healthcare field, in roles such as clinical medical assistant or phlebotomy technician. Courses in the construction field are also a popular choice, covering subjects like HVAC technology, plumbing, and welding.

The training is not free, though. Participants are responsible for one-third of program costs; out-of-pocket tuition averages around $800. Though financial aid is available, this modest price of enrollment may select for students who are serious about finishing their programs.

The state of Virginia contributes another one-third of the program costs if the student completes his or her training. If the student finishes the course and passes the exam to earn the industry-recognized credential, the state funds two-thirds of the program costs. Community colleges therefore receive more money from the state if they successfully graduate FastForward participants and get them into the workforce.

Even though the state subsidizes FastForward, it’s still a relative bargain for taxpayers. The state of Virginia’s contribution per participant is capped at $3,000, and most programs cost far less than that to operate. By contrast, the average community college receives more than $6,000 per student in state appropriations every year. Four-year colleges receive nearly $10,000 per student.

FastForward Enrolls Underserved Students—and Graduates Them

FastForward enrolled more than 11,000 students in fiscal year 2022, the latest year for which data are available. According to the Annenberg analysis, most of these students have been neglected by the traditional higher-education system. Over 60 percent of FastForward participants have never enrolled in a college course for credit. Fewer than 20 percent of enrollees have attained any sort of postsecondary credential. The program thus provides workforce training to those who might not otherwise be able to get it.

FastForward also gives its participants a second chance at starting their careers. Most enrollees are over 30; a fifth are older than 45. While men are underrepresented in the traditional higher-education system, 58 percent of FastForward enrollees are male.

The Annenberg analysis also finds that FastForward enrollees complete their programs at high rates. Nine in 10 participants finish the course they started, while two-thirds pass the exam to earn their industry-recognized credential. While there is room for improvement on exam-passage rates, the numbers compare favorably to completion rates for community colleges overall. Just 30 percent of students who enroll in a credit-bearing community-college program finish.

FastForward’s Most Important Outcome: Higher Wages

But finishing a training program isn’t worth much if the credential doesn’t enhance the student’s earning power. Fortunately, the Annenberg study has good news for FastForward participants.

The authors track individuals before and after they earn a FastForward credential and compare them to individuals who enrolled in a FastForward course but didn’t earn the industry-recognized credential. While the authors observe the boost in wages that FastForward completers enjoy, the comparison to non-completers gives them a baseline: How much would the typical FastForward participant see his earnings increase over the same time period if he didn’t earn a new credential? This method helps isolate the increase in wages that is truly attributable to FastForward.

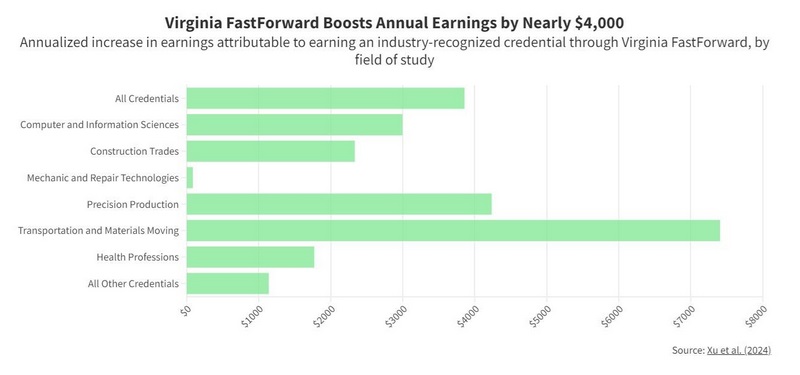

The results are still impressive. Earning an industry-recognized credential increases participants’ earnings by $966 per quarter, which equates to nearly $4,000 per year. That corresponds to a 10-percent increase in earnings for the average FastForward participant.

Not all FastForward courses are equal. Programs in the transportation field—especially the commercial driver’s license—increase earnings by $1,851 per quarter ($7,406 per year). Another strong field is precision production (including welding), which generates an annualized earnings boost of $4,235. Credentials in other fields produce smaller earnings gains, but the impact is positive across the board.

FastForward also increases participants’ employment rates from 78 percent to 80 percent. In addition to boosting employment, FastForward seems to help workers switch industries. Prior to enrolling in their courses, around one-third of FastForward participants were employed in low-wage industries such as retail and food service. After finishing their programs, most participants who worked in these fields moved to jobs in higher-wage industries such as manufacturing and construction.

The results show that FastForward doesn’t just help established workers. It enables people to start new careers.

Can We Build on This Model?

FastForward seems a good deal for both students and taxpayers. The increase in earnings from the typical program exceeds the full cost of operating the course in just eight months, according to the Annenberg study. This is a far better return on investment than most associate’s degrees or other “typical” community-college programs.

However, community colleges’ other offerings receive generous federal support through the $30 billion Pell Grant program, among other channels. In fact, Pell Grants fully cover tuition bills for many community-college students enrolled in degree programs. FastForward students, however, cannot use Pell Grants to pay their tuition. There are some state-based financial-aid programs to help, but the federal government still has its finger on the scales in favor of traditional higher education.

There is some momentum to change that. A bipartisan proposal introduced last year would expand Pell Grant funding to workforce-training programs that generate large increases in wages. Many (though not all) FastForward courses could qualify. The expansion is a relative bargain: Just $1.5 billion over a decade would enable 100,000 students per year to access workforce training. The bill pays for itself by limiting certain wealthy universities’ access to federal student loans, which are currently a loss-maker for the government.

There is a danger, of course, that introducing federal funding might also introduce federal bureaucracy and spoil what makes FastForward work so well. The requirement that students cover some tuition out of pocket gives participants skin in the game, which could disappear if Pell Grants began to cover the cost.

Still, the instinct to level the playing field between traditional higher education and workforce training is a good one, and policymakers ought to consider how to better support programs like FastForward while preserving what makes them work.

Conclusion

Virginia FastForward serves individuals whom the traditional higher-education system neglects, fills needed occupations, and boosts its participants’ earnings for a relatively small cost. Other states should consider what they can do to replicate the Old Dominion’s successful model. Workers seeking a career transition, too, should look at short-term workforce education as a potential path towards finding a better job.