A recent hearing of the House Ways and Means Subcommittee on Work and Welfare confirmed that the financing of the nation’s Unemployment Insurance (UI) system is enormously complicated. Even the name of the federal payroll tax (FUTA—short for the Federal Unemployment Tax Act that authorizes it and pronounced “few-ta”) is confusing. That complexity sent subcommittee members searching for simple-sounding metaphors to explain how the system works. For example, Rep. Gwen Moore (D-WI) wondered aloud whether states that did a “remarkable job” in helping the unemployed return to work received less federal administrative funding as a result, amounting to “you bite your hand to spite your face, or whatever.”

Another metaphor did a far better job capturing a key theme of the hearing: that states need more federal resources to improve the administration of UI benefits—before another recession causes claims to spike. As Democratic witness Jennifer Phillips of Georgetown University summarized, “you can’t fix the roof” without sufficient administrative funding. That echoes former Ways and Means Committee Chairman Charlie Rangel (D-NY), who often argued that government programs need to fix the roof on sunny days.

Both parties admit that UI failings were on full display during the pandemic. Democrats recall that claimants had to wait weeks, and sometimes months, to receive benefit checks as states were overwhelmed by record claims. Republicans stress that systems were unable to stop criminal gangs from fraudulently claiming massive amounts of benefits, which some experts believe resulted in a staggering $400 billion in fraud and misspending out of $900 billion in benefits paid. Both sides recognize that failing to provide sufficient funding—and oversight—to improve UI’s administrative capacity risks repeating those failures.

But first, lawmakers must determine what sufficient administrative funding means, who should get it, and how to pay for it. Current formulas—under the UI program’s “Resource Justification Model” (RJM)—provide more federal administrative funds to states with more UI claims. But that shortchanges states that help UI claimants quickly return to work, as Rep. Moore noted. And it does nothing to anticipate rising needs in the next recession when, if the pandemic is any guide, criminals will once again attack federal benefits.

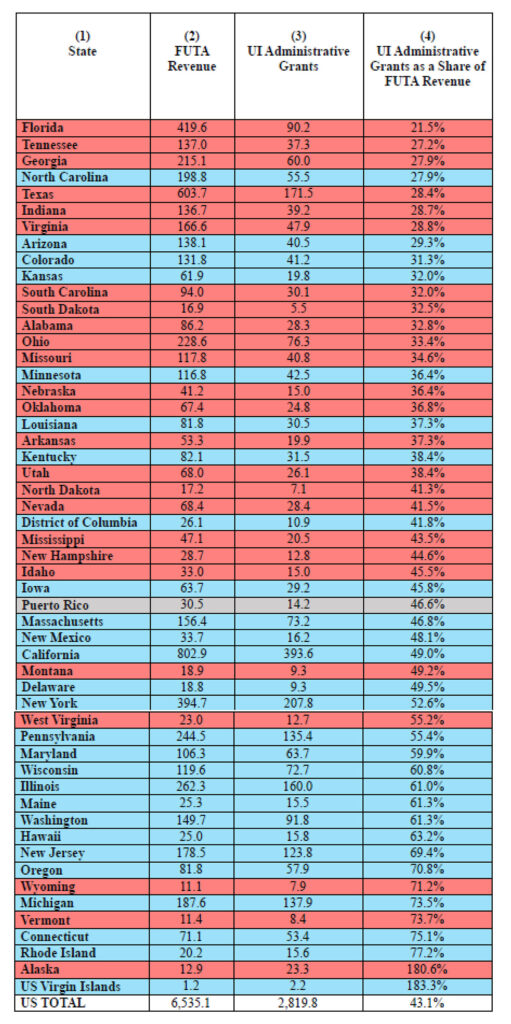

The table below shows how current rules shortchange states in “sunny” years like 2022—the most recent year of data—when they should be improving systems to prepare for the next recession. Instead, as Phillips testified, the “Resource Justification Model makes it difficult to have extra resources to be able to work on modernization efforts.” That’s putting it mildly. In 2022, 51 of 53 states (UI counts the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the US Virgin Islands as “states”) paid more in FUTA payroll taxes than they received back in federal funds to administer UI benefits. Only Alaska and the US Virgin Islands were “winners” under this formula in FY 2022.

Source: US Department of Labor. Red and blue reflect the party of the state’s governor in 2022 (or, in the case of DC, the mayor). The governor of Puerto Rico is a member of the New Progressive Party.

The table displays a partisan tilt in the share of federal revenues returned, with red states tending to receive smaller shares than blue states. But the bigger picture is that hardly any states are winners under this system, whether red or blue. Counting all other federal UI funds provided to states (including for the Employment Service, the Extended Benefits program, and other purposes) adds only Connecticut, New Jersey, New Mexico, and Wyoming to the “winners” column in FY 2022.

It’s not just a “sunny years” issue, either. Reviewing the same data for FY 2020—which included the highest weekly unemployment benefit claims ever—shows only 11 states received more in federal administrative grants than the FUTA taxes they paid that year. Adding in all other federal UI funds increases the number of “winner” states to 32. But that begs the question: Why, in the worst year for unemployment claims ever, were 21 states still losers under federal funding formulas?

That suggests the proper solution goes well beyond simply appropriating more federal funds, and instead involves better connecting revenue with administrative funding. Instead of trying to force more money through the current flawed system, a better approach would be to allow individual states to determine how much they need to administer UI and then collect and spend that amount. That change would keep program funds from getting lost in DC, while holding states accountable for real results—so that, when sunny days turn stormy, the roof doesn’t leak like a sieve again.