“Isn’t divorce less of a big deal for kids these days?” A colleague’s wife asked me this question as we hiked down Parkman Mountain last summer, while taking a break from an academic conference. She asked the question after she learned that I studied American families. “After all,” she added, “we’re more accepting now of all sorts of families.”

My hiking partner’s theory was this: because kids in nontraditional families are less likely to feel ostracized or stigmatized nowadays, they are also less likely to be harmed by family breakdown than they would have been a half-century ago.

Her view is increasingly common. Many people, especially well-educated, left-leaning people like my Maine conversation partner, think marriage and a stable family are less important for children and adults in the contemporary world than they once were. Either because they adhere to progressive ideas about family diversity—the notion that love, not marriage, makes a family—or the individualistic belief that flying solo is just as good as flying with a copilot while raising kids, growing numbers of Americans now discount the value of stable marriage for children.

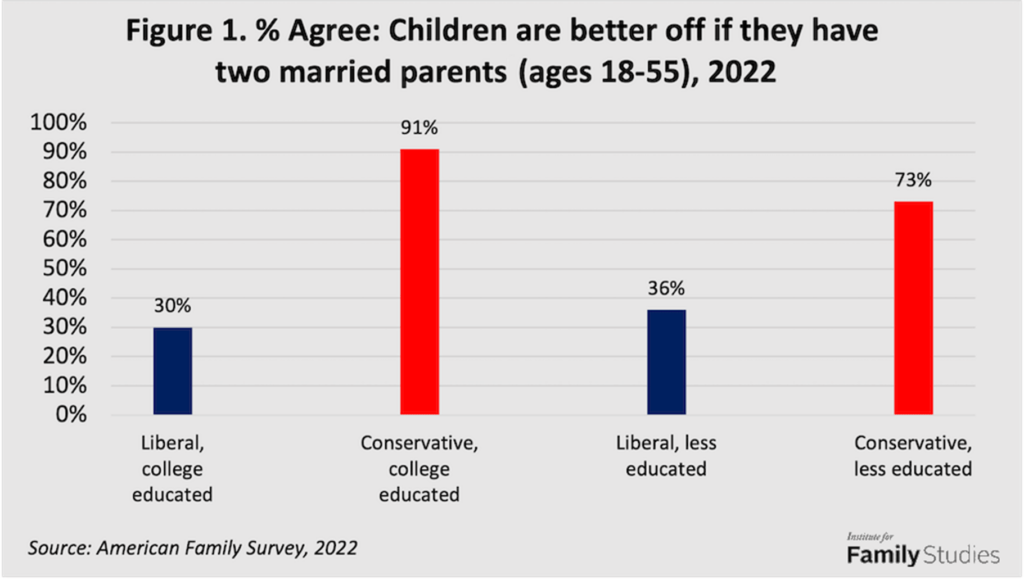

For instance, from 2006 to 2020, the share of adults who said it is “important” that unmarried couples who have had a child together “legally marry” fell from 76 percent to 60 percent, according to Gallup. This trend was especially pronounced among well-educated liberals, according to the 2022 American Family Survey. Only 30 percent of college-educated liberals aged 18-55 said “children are better off if they have married parents,” as did only 36 percent of American liberals without a college degree. By contrast, more than 70 percent of conservatives—especially college-educated conservatives—took the view that marriage matters for children. But in general, Americans, and especially the most privileged liberals, increasingly discount the value of married parents.

No doubt these attitudinal trends are shaped in part by the progressive family ideas coming from the academy and media. Discussing the end of her marriage, University of San Francisco professor Lara Bazelon recently wrote in the New York Times that divorce is “liberating, pointing the way toward a different life that leaves everyone better off, including the children.” Her article is one of many such essays that mainstream media outlets have published recently.

But hiking down the Maine mountain that summer day, I gently rejected this kind of thinking, noting to my interlocutor that my reading of the social science tells us that a stable, married family still gives children a leg up in life. I was thinking of surveys of family scholarship like this one from the Brookings-Princeton journal, Future of Children, reporting that “most scholars now agree that children raised by two biological parents in a stable marriage do better than children in other family forms.” This week an important new book, The Two-Parent Privilege: How Americans Stopped Getting Married and Started Falling Behind, by Brookings economist Melissa Kearney, underlined this conclusion. In the book, Kearney, who also teaches economics at the University of Maryland, conveys “mounds of social science evidence [showing] how the odds of graduating high school, getting a college degree, and having high earnings in adulthood are substantially lower for children who grow up in a single-mother home.”

If anything, Kearney and the Future of Children’s conclusions may undersell the value of a stable, two-parent family for kids today. Evidence mounts that the value of marriage and a stable family life for children is not only enduring but increasing. In the last year, a number of studies spotlighted the tightening link between family structure and the educational, social, and economic welfare of America’s children. For instance, a new report from the Institute for Family Studies by Wendy Wang, Spencer James, Thomas Murray, and me shows that the benefit of hailing from an intact family rose across generations, from baby boomers to millennials. We found that a 14-percentage-point gap in college graduation between intact families and non-intact families among boomers grew to 23 percentage points for millennials. Our results parallel a study published last October by economists Adam Blandin and Christopher Herrington on college graduation trends from 1995 to 2015, which found that “family type has become an increasingly important predictor of college completion over time.”

These findings complement other research telling a similar education-related story earlier in the life cycle for kids. A study headed by Kathleen Ziol-Guest at New York University exploring the link between family structure and “educational attainment”—how many years of schooling children complete—found that from the late 1960s to the 1990s, this link grew stronger: “the estimated [negative] relationship between the single-parent family structure variable and educational attainment more than tripled in size.”

The family-structure gap dividing children and young adults is also growing on the financial front. A recent study from scholars at Peking University and New York University found “children who lived in single-headed families experienced greater increase in childhood income volatility” from the 1970s to the 1990s, meaning single-parent families and their children were subject to greater income swings in the 1990s than earlier decades even as the study found no increase in income volatility for children raised in two-parent homes. Income volatility matters because it often translates into families having less money to cover important costs such as rent, food, or child care; in the words of the study’s authors, Airan Liu and Siwei Chang, it “can also stress parents and compromise their ability to provide high-quality child care.”

Likewise, the new Institute for Family Studies report found that the advantage associated with being raised in an intact family for young adults’ odds of reaching the middle class or higher as thirtysomethings has grown in recent generations. For boomers who entered their thirties around 1990, coming from an intact family boosted their odds of reaching the middle class or higher by 16 percentage points. By contrast, millennials who entered their thirties in the last decade and grew up in a stable family saw their odds boosted by 20 percentage points. We again have yet more evidence that, at least for some outcomes, the advantage of being raised in a stable, married family may be growing for today’s children and young adults.

Why are studies showing that the benefits of marriage and a stable family for children today are larger than in the past? Is it because marriage is increasingly the preserve of educated and affluent Americans, thereby skewing the results? Well, no. The studies referenced above control for factors like race and parental education, and still find a premium associated with being raised in an intact family. So that’s not likely the story.

Three other factors seem more likely explanations. First, dads are more involved in their kids’ lives than they used to be. This means children in married families generally have the benefit of more fatherly attention today than they did a few decades ago.

Second, as more married women work, the financial benefits of marriage for kids continue to rise. This means married parents can devote relatively more money today to the rising costs of parenthood—from tutoring to travel sports to tuition for college—than can parents in nontraditional families, especially single-parent ones.

Third, a new study published in Demographic Research indicates that couples are initiating divorce or family breakups for less serious reasons than in the past, which means that more kids today are exposed to “low-conflict” family dissolutions (where the relationship breaks up for reasons unrelated to domestic violence or recurring fights). “Unfortunately, these are the very divorces [and breakups] that are most likely to be stressful for children,” because they seem relatively incomprehensible or unneeded to kids, as family scholars Paul Amato and Alan Booth noted in their book A Generation at Risk. My Maine conversation partner would undoubtedly be surprised to learn that the evidence continues to mount against the theory that family instability is not “a big deal for kids these days.”

What we have, then, is a troubling family irony unfolding in the United States. On the one hand, Americans—especially well-educated liberals who dominate the discourse and policy related to family life—increasingly discount the value of marriage and stable, two-parent homes for children. On the other hand, the actual benefits of marriage and a stable family for kids appear to be mounting. What’s especially ironic is that the very group of Americans most likely to deny or minimize the value of marriage—college-educated liberals—are much more likely to enjoy the benefits of a stable family life than are less-advantaged Americans.

The scholars, journalists, and policymakers who drive so much of our family discourse and policies today ought to notice this new family science and bring it to broader attention—in schools, media, and other venues. Doing so might not only reverse the devaluation of marriage and stable family life among the public at large but also increase the odds that more mothers and fathers will give their kids the benefit of being raised by married parents.

W. Bradford Wilcox, professor of sociology and director of the National Marriage Project at the University of Virginia, is a nonresident senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. He is the author of Get Married: Why Americans Must Defy the Elites, Forge Strong Families, and Save Civilization (forthcoming from Harper Collins).