The share of American men and women who think that marriage and a stable family are not important for children in our contemporary world is growing. Either because they adhere to progressive ideas about family diversity, discount the unique value of marriage, or believe that single parents are just as capable of raising children as two parents, more and more Americans seem to think stable marriage is not important for children today.

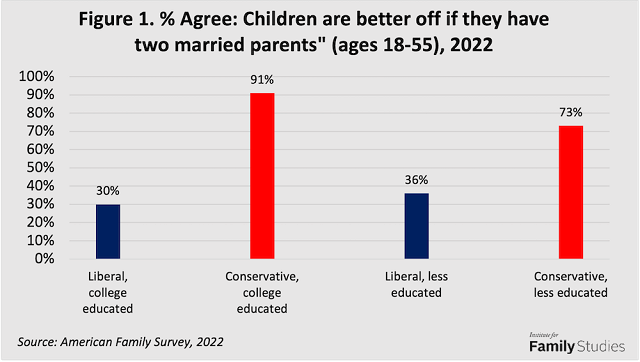

For instance, from 2006 to 2020, the share of adults who said that it is “important” for unmarried couples who have had a child together to “legally marry” fell from 76% to 60%,1 as did the share of adults who say divorce is “unacceptable.”2 The 2022 American Family Survey indicates that college-educated liberals are especially likely to discount the value of marriage for children. Specifically, among adults ages 18 to 55, only 30% of college-educated liberals said that children are “better off” with married parents, the lowest share of any group in the survey. By contrast, 91% of college-educated conservatives think that children are better off if they have married parents. But because a majority of college-educated Americans lean left, the drift among more well-educated men and women in the United States has been towards the view that marriage is not important for children.

Shifts in public opinion about the value of stable marriage like the ones detailed above, including for children, have been driven in part by elite discourse on the subject. In recent years, we’ve witnessed a surge in media commentary minimizing or denying the effects that divorce, single parenthood, and family instability have on children. For instance, one University of San Francisco professor, Lara Bazelon, recently wrote in the New York Times that divorce “is painful and heartbreaking. But it can also be liberating, pointing the way toward a different life that leaves everyone better off, including the children.”3

Meanwhile, some family scholars have speculated that “the consequences of divorce should become smaller when the divorce rates increase, because the higher these divorce rates are the more normal divorce becomes and thus the lower the level of stigmatization.”4 In other words, the negative effects we see from divorce, even those affecting children, will disappear as the stigma associated with divorce diminishes. Others contend the social science tells us that family structure per se does not matter for child well-being, only the quality of family relationships. Sociologist Pamela Braboy Jackson from Indiana University put it this way to The Atlantic: “All of our research points to the fact that it’s the quality of the relationship that matters, and the handling of communication and conflict, and the number of people in the household is not really the key,” adding, “Just because family structure is different doesn’t mean that family operates any differently.”5

Recent Research on Family Structure and Children

However, a growing body of evidence not only contradicts the conventional wisdom, journalistic narratives, and academic assertions that a stable, married family is of little or no importance to children but also indicates something quite different. In fact, marriage and a stable two-parent family appear to matter more than ever for children on a range of outcomes. Recent research suggests that an intact family is increasingly tied to the financial, social, and emotional welfare of children—and family instability is more strongly linked to worse outcomes for kids than it used to be. The upshot for children is that marriage not only still matters, but it seems to matter more than ever. Children who have the benefit of two parents are comparatively more advantaged today than they were in previous decades.

Consider children’s educational attainment. In Education Next, a research team led by Kathleen Ziol-Guest at New York University explored the link between family structure and “educational attainment”—or how many years of schooling children complete across America. From the late 1960s, when family breakdown was more unusual, to the 1990s, when it was common, that link did not weaken; instead, it grew stronger. The researchers concluded: “the estimated relationship between the single-parent family structure variable and educational attainment more than tripled in size.”6 The tightening link between family structure and education does not just apply to educational attainment, it also extends to student behavior. A recent analysis by Nicholas Zill and Brad Wilcox found that “rates of school contact for student misbehavior are nearly twice as high among students living with separated or divorced parents as among those living with stably married parents.” Zill and Wilcox also found that school suspensions or expulsions are almost three times as high for children living in non-intact families, compared to children in intact, married families. Moreover, their results indicate “the relative risk faced by students from non-traditional families has actually increased” from 1996 to 2019 when it comes to school suspensions and expulsions, as well as school reports of student misbehavior. To be sure, on some outcomes, like repeating a grade, Zill and Wilcox found that the link was essentially stable over time. But they found no evidence that the link between family structure and student outcomes is diminishing.7

The Long Reach of Family Instability on Young Adults

But is there any evidence that family instability is also consequential for young adults? To answer this question, we investigate the association between family structure and college graduation, as well as family structure and economic success.

We used panel data from the 1979 and 1997 cohorts of the National Longitudinal Study of Youth (NLSY). The NLSY79 consists of a nationally representative sample of 12,686 men and women born between 1957 to 1964 living in the U.S. (the youngest Baby Boomers). This survey started in 1979, when the respondents were ages 14-22, and the most recent round of interviews was in 2020. Similarly, the NLSY97 started in 1997 with a new nationally representative sample of 8,984 adolescents who were born between 1980 to 1984 (the oldest Millennials). The survey respondents were ages 12 to 16 when the survey began in 1997 and were in their late 30s in the latest wave in 2020.

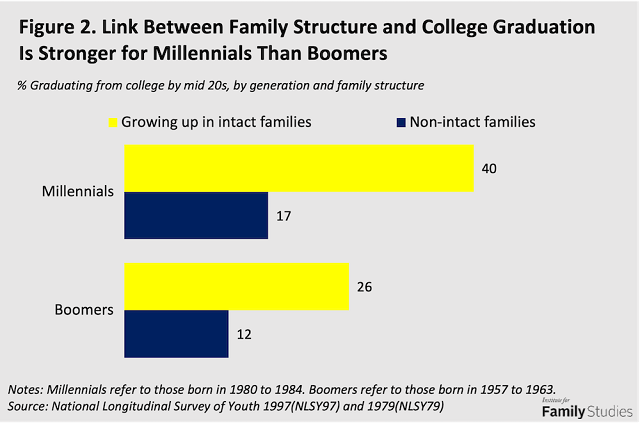

We compared the two cohorts, Boomers and Millennials, at the same life stage when they reach their mid-twenties. Our analysis suggests that family structure’s association with key outcomes for young men and women is growing. For Boomers who were born in the late 1950s and early 1960s, 26% who grew up with both their biological father and mother had a college education by their mid-20s; the share was 12% among Boomers who grew up in non-intact families. The gap among Millennials is bigger. When Millennials were in their mid-20s, 40% who grew up with both biological parents had a college degree, compared to 17% from non-intact families.

Some of these differences could be attributed to selection. Growing up in an intact family has become less common in the past few decades, especially for children from lower-income and less-educated families. A large majority of Boomers (75%) in the NLSY79 sample who reached their mid-20s were raised in an intact family with both biological parents present, but only about half of 20-something Millennials (52%) in the NLSY97 sample were from an intact family.

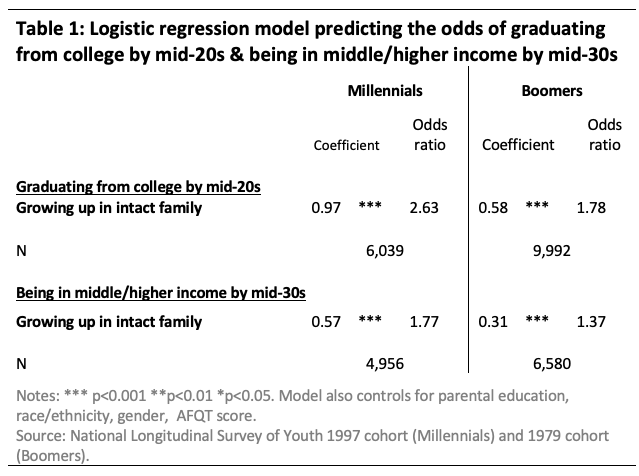

But even after controlling for a range of socioeconomic factors—race, gender, parental education, and AFQT score (a measure of respondent’s general knowledge)—growing up in an intact family increases Boomers’ odds of graduating from college by 78 percent. But Millennials who reached their 20s in the 2010s got a bigger boost, of approximately 163%, in their odds of graduating from college when they came from a stably married family. Moreover, ancillary analyses indicated that the interaction between family structure and cohort8 upon college graduation was statistically significant, which suggests that the relationship between family structure and college graduation is stronger today than it was for Boomers.

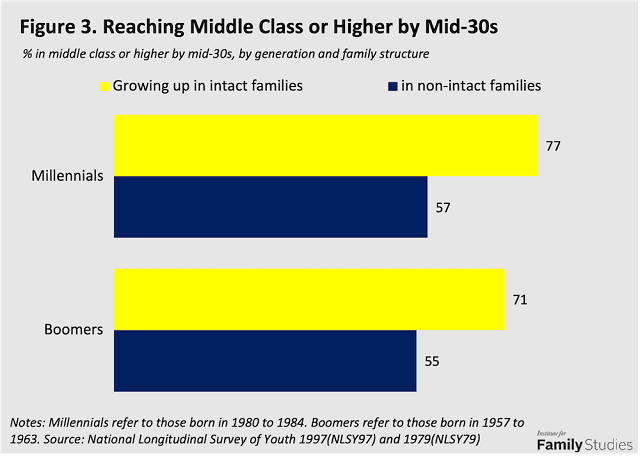

A similar generational story appears when it comes to children’s odds of realizing the American Dream when they reach adulthood. Some 77% of Millennials from intact families reached middle or higher income by their mid-30s, which is 20 percentage points higher than their peers from non-intact families. The gap among Boomers was smaller (16 percentage points), such that 71% of Boomers from intact families achieved that same level of economic success in their mid-30s, while only 55% of those from non-intact families did so.

After controlling for a range of socioeconomic factors, the data indicate that for Boomers who reached their 30s in the late 1990s, coming from an intact family only boosted their odds of reaching the middle class or higher by 37 percent. By contrast, Millennials who reached their 30s in the last decade and had the benefit of growing up in a stable family saw their odds of realizing the American Dream increase by 77%, compared to their peers who were raised in a non-intact family.9 Moreover, ancillary analyses indicated that the interaction between family structure and cohort upon economic success was statistically significant, which suggests that the relationship between family structure and economic success is stronger today than it was for Boomers.

When we focus on economic success as measured by reaching the upper-third of income, we see a similar story. Almost four-in-ten Millennials (42%) from intact families are affluent by the time they are in their mid-30s, compared with 24% of their peers from non-intact families. The gap among Boomers is smaller, with 36% of Boomers from intact families and 22% from non-intact families reaching affluence by their mid-30s (see Appendix for details).

After controlling for socioeconomic factors, Millennials’ odds of being in the third highest income bracket in their 30s are 77% higher for those who grew up in an intact family with both biological parents. For Boomers in their 30s, growing up in an intact family boosted their odds of being affluent by 42 percent.

So again, we have yet more evidence—this time on the economic front—that the benefit of being raised in a stable, married family may be growing for children and young adults in the United States.

Why Do Marriage and Family Structure Matter More Than Ever?

Why might stably married parents be more consequential than ever for children? Beyond the fact that married individuals are more selective than they once were, we suspect three factors help explain this family advantage.

First, dads today are more involved in their kids’ lives than they used to be.10 This means children in married families have the benefit of a lot more paternal attention today than they did a few decades ago. In fact, a recent Vanderbilt study found that time devoted to children increased most in recent years among two-parent families.11

Second, there is evidence that the traditional economic advantage that married families enjoy over single-parent families has grown in recent years. The Vanderbilt study found that expenditures upon children have grown most among college-educated, two-parent families.12 Another new study from scholars at Peking University and New York University found “children who lived in single-headed families experienced greater increase in childhood income volatility” in recent years. In other words, single-parent families have recently been subject to greater up-and-down swings in their income. This matters because income volatility is not only associated with less consistent ability to cover the expenses associated with raising a child but also greater parental stress.13

Third, the rise in divorce and family breakdown over the last half century means that children are experiencing a rising number of low-conflict separations now as compared to a few decades ago. A 2017 study of family instability and college graduation in Europe found that such instability was more strongly linked to lower rates of graduation in recent years. The family scholars who did the study suggested that a rise in low-conflict separations in Europe is the explanation. While the separation of high-conflict parents may bring psychological relief to children, the separation of low-conflict parents does not. Indeed, research indicates that it is far more damaging to a child who cannot comprehend or accept why a relatively low-conflict parental relationship has ended.14 In their words, as

more and more low-conflict families split up… the negative effects of breakup are encountered more frequently. At the population level, the negative consequences outweigh the positive, and the overall (average) negative effect becomes stronger as a result.15

Conclusion

This Institute for Family Studies brief suggests that the value of marriage and a stable family life may well be increasing for children in the United States. Recent research indicates that the economic well-being, educational attainment, and school behavior of children are more tightly linked to family structure than ever. This research brief finds a similar story when it comes to college graduation and young adult financial success insofar as the collegiate and financial advantage associated with coming from an intact family has increased for young adults in recent years, compared to young men and women who came of age in the 1970s and 1980s. In sum, there is growing evidence that a stable married family not only still matters, but may matter more than ever for our children and for young adults in America.

Download the full research brief, including the Appendix, here.

Brad Wilcox is professor of sociology and director of the National Marriage Project and is the Future of Freedom Fellow at the Institute for Family Studies. Wendy Wang is the director of research at the Institute for Family Studies. Spencer James is associate professor of family life at Brigham Young University and a senior fellow at the Institute for Family Studies. Thomas Murray is a research associate at the Institute for Family Studies.

1. Gallup, “Marriage: Gallup Historical Trends,” 2022.

2. Gallup, “Moral Issues,” In Depth Topics A to Z.

3. Bazelon, Lara. “Divorce Can Be an Act of Radical Self-Love,” The New York Times, September 30, 2021.

4. Dronkers, Jaap, Matthijs Kalmijn, and Michael Wagner. “Causes and Consequences of Divorce: Cross-National and Cohort Differences, an Introduction to This Special Issue.” European Sociological Review 22, no. 5 (2006): 479–81.

5.Angela Chen, “The Rise of the 3-Parent Family,” The Atlantic, September 22, 2020.

6. Kathleen M. Ziol-Guest, Greg J. Duncan, and Ariel Kalil. 2015. “One-Parent Students Leave School Earlier.” Education Next 15.

7. Nicholas Zill and Brad Wilcox, “Strong Families, Better Student Performance,” Institute for Family Studies Blog, August 26, 2022.

8. Statistically, this means we harmonized the two NLSY cohorts’ (1997 and 1979) data, created a dummy variable indicating which dataset each observation came from, and then entered an interaction term that examined whether the relationship between family structure and the outcomes examined (college graduation and economic success) differed by cohort.

9. NLSY79 and NLSY97. Regressions controlled for gender, race, parental education, AFQT score, family income growing up.

10. Ross Parke, Fatherhood. Boston: Harvard University Press, 1996; W. Bradford Wilcox and Kathleen Kovner Kline. Gender and Parenthood. New York: Columbia University Press, 2013.

11. Adam Blandin and Christopher Herrington, “Family Heterogeneity, Human Capital Investment, and College Attainment,” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 14, no 4: (2022): 438-478.

12. Ibid.

13. Airan Liu, et al., “Family Structure and Cohort Trend in Childhood Family Income Volatility,” Socius 9 (2023).

14. Kreidl, Martin, Martina Štípková, and Barbora Hubatková. “Parental Separation and Children’s Education in a Comparative Perspective: Does the Burden Disappear When Separation Is More Common?” Demographic Research 36 (January 5, 2017): pp. 74-5.

15. Ibid, p. 75.